At 29 years old in the spring of 2011, Britney Spears had sold millions of albums, released five No. 1 hits, completed multiple world tours, bore two children, and endured intense media scrutiny of her darkest moments.

But on the set of her video for top-ten hit “Till the World Ends,” she wasn’t allowed to use the bathroom when she wanted to.

MTV’s behind-the-scenes footage shows a handler making the request on Britney’s behalf to the music director, who mentioned the amount of money the bathroom break would cost.

Before you write that off as a typical occurrence in the entertainment industry, consider this passage from Spears’ new memoir, “The Woman in Me,” which describes her reaction to Madonna holding up a video shoot for hours to fix a seam on her suit.

“I didn’t even know taking so much time for oneself was an option,” Spears writes of the event, which occurred in 2003 on the set of her video for “Me Against the Music,” featuring Madonna. “It was an important lesson for me, one that would take a long time for me to absorb: she demanded power, and so she got power. … I hoped I could find ways to do that while preserving the parts of my nice-girl identity that I wanted to keep.”

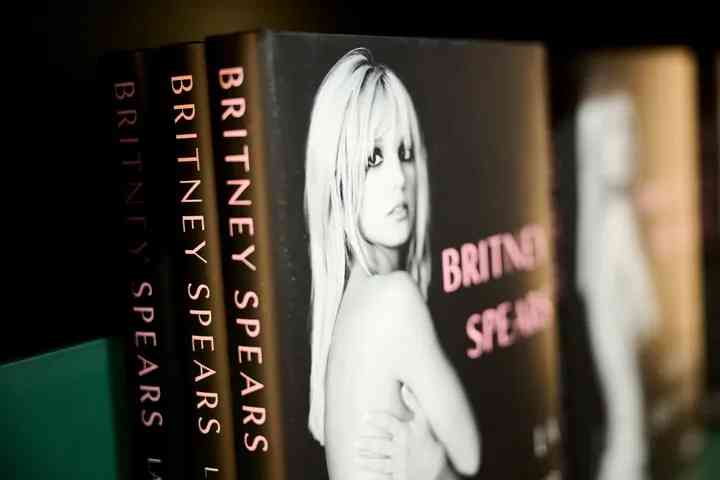

Those moments of reflection are what make “The Woman in Me” a compelling — and devastating — read. Forget the “juicy” tidbits that have been splashed across headlines leading up to the book’s release on Oct. 24. The memoir is not a tabloid tale or a Justin Timberlake takedown.

The most gripping part of the book is Spears’ account of the horrific treatment she faced under the 13-year conservatorship led by her father. She adeptly lays out the compounding trauma of that experience and previous years of cruelty and manipulation at the hands of men and media. Any skepticism about her mental state interfering with her ability to present her story with depth and insight will be quickly quelled. (Journalist Sam Lansky was the ghostwriter for the memoir, according to Vox.)

First, Spears provides new details of her sometimes volatile childhood in Kentwood, Louisiana, including a breakdown of her family’s generational trauma. Next, she recounts her rise from precocious child performer and “Mouseketeer” to superstar, but doesn’t spend much time on this period, which is a little jarring.

Yes, Spears became famous quickly with the help of the music industry machine. But she also worked extremely hard and performed at a very high level for years (revisit some of the choreography and acrobatics in early videos and tours). So often, women artists do not spend enough time unpacking their own artistic strengths in their books and documentaries. The closest Spears comes to this in her memoir is sharing the pride she felt while making the critically acclaimed “Blackout” album in 2007, and her 2016 album, “Glory.”

As Spears bravely reveals the impact of difficult life events ― including the abortion she had while dating Timberlake, the postpartum depression she endured as a young mother stalked by the paparazzi, and the breakdown that prompted the start of the conservatorship in 2008 ― she writes with acute self-awareness.

“I became a robot. But not just a robot — a sort of child-robot,” she writes. “I had been so infantilized that I was losing pieces of what made me feel like myself. … I became more of an entity than a person onstage.”

Spears explains how the conservatorship stole her joy and creativity as a performer. Because she suffered in silence for so long, it feels almost revolutionary when she speaks directly to her loyal fans about this period of “sleepwalking” through her shows.

Even if you’ve watched the documentaries, read the articles and heard Spears’ court testimony about the conservatorship, the book will surprise you with horrors about her father’s control and her family’s complicity. Spears conveys the humiliation of being told what to eat, where to go, what to do with her body, when to see her children. One of the most chilling parts of the book is her account of a forced stay at a psychiatric facility in 2019, where she was put on lithium.

Those harrowing details dismantle the long-held perception that Spears was an unfit mother whose life was saved by the conservatorship. It’s clear why she has shown such hostility toward her family.

Despite those dark chronicles, the book is not all doom and gloom. At times, Spears writes with humor, poking a little fun at herself (“I was a bad dresser — hell, I’m still a bad dresser”) and others, including ex-husband Kevin Federline (“He really thought he was a rapper now. Bless his heart.”).

She also talks about still struggling with whether she should perform again; you get the sense that it might not be good for her mental health.

By the time you reach the end of the book, you better understand Spears’ antics on Instagram — and, frankly, don’t care to criticize given what she has endured. The endless modeling of clothes follows 13 years of being told how to dress. The repeated dancing follows 13 years of being told when and how to perform. The wielding of fake knives follows 13 years of being confined or medicated after the slightest attempt to rebel.

“It’s been a while since I felt truly present in my own life, in my own power, in my womanhood,” Spears writes at the end of the book. “But I’m here now.”

By the end of the book, you actually do believe her.