The phrase shows up in popular culture as synonymous with fatalistic warning, but it has a much deeper meaning for Jews.

Super-star rappers French Montana, Post Malone and Cardi B made it the title of their 2019 hit. Rock artist Paul Simon mentioned it in his hit single, Kodachrome. Rembrandt immortalised it in his painting, Belshazzar’s Feast, and he included in that work a “word puzzle” from the rabbis of the Talmud. It’s been satirised, politicized, popularised, set to music, made into the title of scores of books, bands and tunes. For more than 2,000 years, its imagery has terrified and mesmerised readers, even though most people, I suspect, don’t understand what it truly means or where it comes from. What is this mysterious idea striking fear in people’s hearts and making huge dents in high and low culture for centuries? It’s the timeless story of the writing on the wall.

When we use it in everyday speech, we might say, “You need to read the writing on the wall,” or “I can read the writing on the wall.” We generally mean by this that we can detect something terrible that will happen in the near future. There seems to be universal agreement that to read the writing on the wall means to brace oneself, soberly and stoically, for the worst. However, this popular use of the phrase distorts its original meaning. In the Book of Daniel, the source of the phrase, something quite different is happening.

Some background is in order before we look at the original story of the writing on the wall. Daniel is a Jew exiled to Babylonia during the military campaign of King Nebuchadnezzar against the Judean State in 586 BCE. According to the first four chapters of his eponymous book, he and his three friends are part of an elite corps of exiles pressed into a royal training program to serve the king and state. The four young men distinguish themselves with a string of divinely aided successes, demonstrating extraordinary gifts of dream interpretation and intelligence, all while fiercely maintaining their Jewish identities and personal integrity. With strong echoes of the “exile-to-palace” climbs of Joseph (and, to some degree, Esther), Daniel and his friends twice interpret the king’s ominous dreams of personal and imperial disaster and apocalyptic regime change, while also exhorting him to repent before God. The “hat trick” that secures their high status with the king is when the three friends are thrown into a fiery furnace but survive the ordeal with nary a scratch on them. (The story of Daniel in the lion’s den, a similar miraculous escape from a pit of death, comes later in the book.)

With this in mind, we enter the scene of a huge party being held by Belshazzar, the son of Nebuchadnezzar, who takes over when his father is banished. What do we first notice?

Under the influence of the wine, Belshazzar ordered the gold and silver vessels that his father Nebuchadnezzar had taken out of the temple at Jerusalem to be brought so that the king and his nobles, his consorts and his concubines could drink from them … They drank wine and praised the gods of gold and silver, bronze, iron, wood and stone. (Daniel 5:2-4)

This was, for the ancient Jews watching, truly vile. It was bad enough that the Babylonians, under the leadership of Belshazzar’s father, exiled the Jewish people, destroyed their holy Temple, and stole the sacred vessels … but using them to get more drunk and to worship false gods? Even God, who according to biblical theology used the Babylonians as a means by which to punish the Jews for their sins, would have no reason to want that. Enter the writing on the wall:

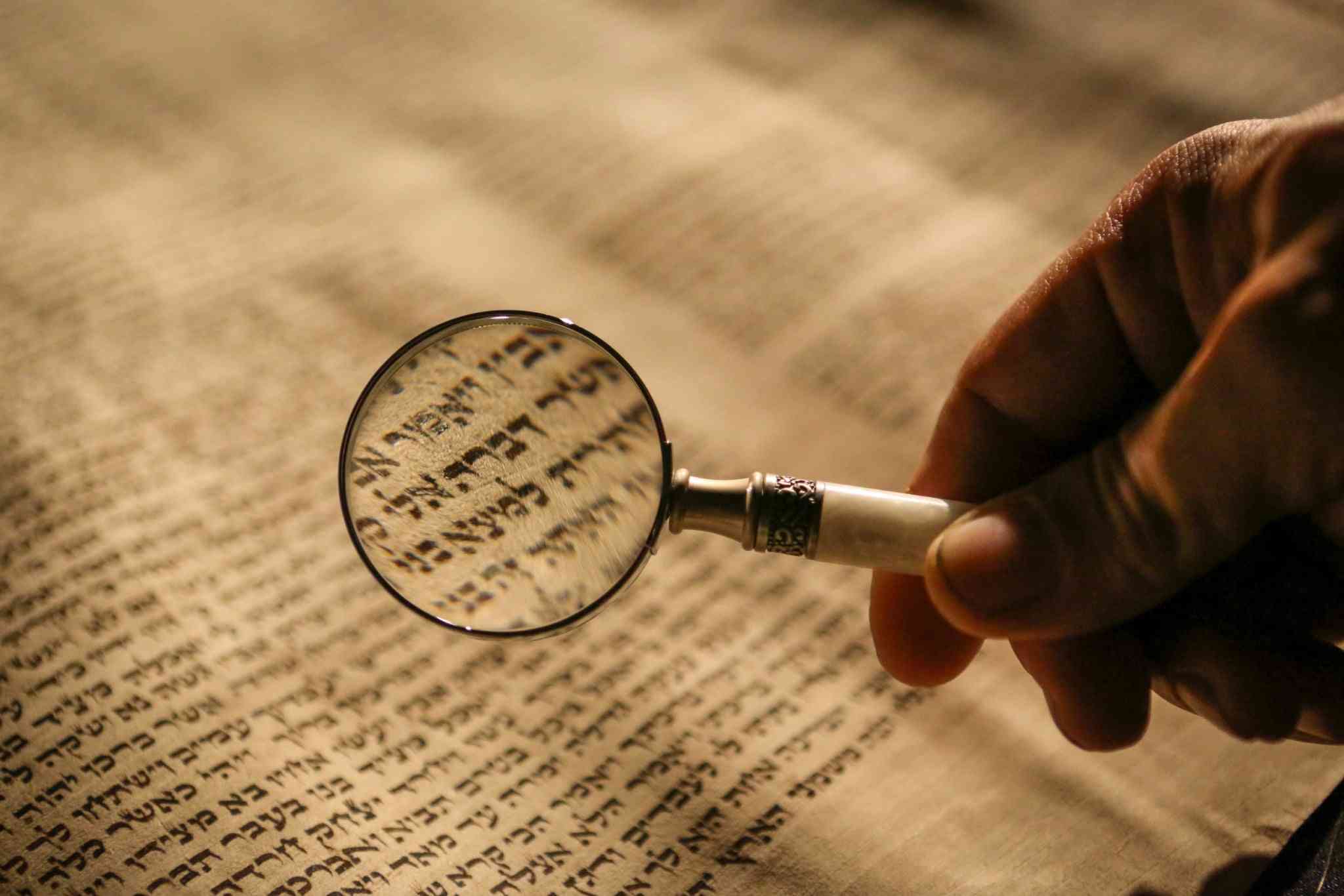

Just then, the fingers of a human hand appeared and wrote on the plaster of the wall of the king’s palace opposite the lampstand, so that the king could see the hand as it wrote. (Daniel 5:5)

The king calls for his magicians and wise men to read and interpret the writing but, predictably, they can’t. Only that magnificent court Jew, Daniel, is able to. After excoriating Belshazzar for his arrogance and impudence before God, he reads the now-famous words on the wall:

Mene Mene Tekel U-Pharsin

Our hero decodes God’s dire warning to the king:

God has numbered [the days of] your kingdom and brought it to an end; you have been weighed in the balance and found wanting; your kingdom has been divided and given to the Medes and Persians. (5:26-28)

Spoiler alert: That night, Belshazzar is killed, presumably the victim of a military campaign that brings his enemies, the Medes, to power. The writing on the wall foretold truly.

There are clearly similarities between the biblical story and our pop culture appropriation of it. However, the contrasts are what fascinate me.

First, in the popular versions, we usually talk about a person reading the writing on the wall him or herself, to come to terms with a terrible, inevitable reality. But in Daniel, the king and all his advisors can’t read the writing on the wall. Its message is utterly lost to them until Daniel explains it to them.

Second, we generally use the phrase “the writing on the wall” to refer to something which is ominous, but morally neutral. Something bad is going to happen, but it could be deserved or undeserved by us, depending upon our behavior or other circumstances. Yet Daniel’s explanation to the king makes clear that his ruin is the result of his arrogance and hunger for power.

Third, reading the writing on the wall entails preparing for an unpleasant future with no necessary reference to the past that might have brought us there; Daniel’s ominous prediction to Belshazzar is preceded by a harsh admonishment for his miserable past and his villainous deeds.

Daniel is more a classical prophet than a futurist. His job, in this scene, is to reveal Belshazzar’s fate; but even more so, he’s there to offer a damning critique of the king and his society, to force them “to read” the truth about who they have become and where it is leading them.

My teacher, Rabbi Gordon Tucker, wrote about how our revered teacher, Rabbi Abraham Heschel, understood the nature of biblical prophecy:

Heschel … argued that the special aptitude of the prophets was not an ability to predict the future, but rather the deep intuitive sense they had of the devastating effect that earthly injustice has on God’s inner emotional life. As he put it, whoever imagines that God is unaffected by injustice by and to humans, is denying the very essence of religious faith. In this view, what caused prophets to shriek was a shattering and undeniable empathy with the suffering of the Creator.

Daniel is no Jeremiah; he doesn’t shriek at state and society from the margins, he serves them from within, indeed from high within as a member of court. Yet as a passionate lover of God and God’s oppressed people, he refuses to sugarcoat the message of the wall’s writing to appease the king and court. With an empathic rage barely restrained by formality and eloquence, he condemns and supports them by unpacking the dire message written by God’s “hand.”

The story of the handwriting on the wall occupies the realm of biblical mythology and miracle. Removing this literary dressing, we’re left with a message and a mission, a “writing on the wall” of contemporary life, which we Jews are obligated to place incessantly before society: we must speak truth to power. This is difficult to do, especially when it places us at great potential risk; it has always been a fraught endeavor for us, especially in the Diaspora. Like Daniel, we Jews have struggled over many centuries to survive with political cunning under regimes that tolerated us, used us, were hostile to us, and most horribly, tried to destroy us. Even Jewish life in democratic America comes with complicated strings attached. They present us with huge political and moral choices between self-protection and fighting for what is right in the greater society. That’s why Daniel can be such a powerful model for us. He rises so high in the court of the king that the latter calls upon his wisdom and good counsel before all his nobility. Yet the favor that Daniel curries with Belshazzar doesn’t prevent him from severely chastising Belshazzar for his wrongdoing. Daniel serves the king, but he serves God and God’s truth even more.

Particularly in our current American-Jewish Diaspora, we have never felt so well integrated and so fearful for our future and the future of the country. Cast over us is a foreboding that our society is actually writing its own slow demise on our American wall; ironically, it can’t — or it refuses — to read what it has written. Daniel teaches us that, however risky it may be, we Jews must be on the frontlines of using our accrued power, privilege and presence to speak out, protesting what we know are the growing injustices and hatreds that threaten to shatter America in angry, warring, pieces.

Daniel demands of us that we help our society to read the writing on the wall before it’s too late to repair what is broken.