BACK in the days, a genre that grew from being underground, fought its way into becoming one of the most played on radio, night clubs and the streets. Zimdancehall, a genre pregnant with raw talent, made more breadwinners and household names than some people’s favourite local soccer teams.

The genesis

The influx of up-and-coming artistes onto the big scene was so impressive, they commanded a fairly huge listenership that helped them grow into household names. Riddims (literally the Jamaican patois (slang) pronunciation for the English word “rhythm” referring to the instrumental accompaniment to a song) on a reggae/dancehall tip like Need for Speed, Chord 135, Password, High Praises, Ninja Zone, Voice, Tyler Kim, Zimbo Flavour, Bodyslam and One Clan, among others, pushed almost every artiste no matter the stature into producing good if not hit songs. On some of these riddims they would feature an artiste as big as the dancehall president Winky D and then-rising artistes Ras Pompy, Spiderman and Spartexx.

Are the rich worth the trouble?

With the popularity of these riddims and their ability to produce so many hits, good songs and hype, some mbingas (wealthy persons), came into the fold and “bankrolled” the production of the riddims in return of having them named after them. This was, however, not really a bad idea only if artistes got their fair share of the money.

Sadly, this money went to the producers and in return, they (producers) guaranteed mbinga the riddim full of artistes and this meant that either the project was done to satisfy the bankroller or it was hurriedly done so that the producer clears the “debt” for the mbinga.

Monetisation

It has been alleged that the producers would upload these riddims on their YouTube channels and other streaming platforms owning 100% of the production. From the audios to the medleys, all the rights were owned by the producing studio meaning they pocketed all the extra cash that would come through. This saw producers maintaining studios, upgrading equipment and keeping rentals in check.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The war

What seemed to be years of progress and domination cemented by a very good combination of producers and artistes became a breeding war when artistes started shunning “mbinga” personalised riddims. In doing this, the artistes declared that they also wanted the money if the mbingas were to feature on certain projects.

This did not go well with some producers who would have taken payments and promised the bank roller names of the project. In retaliation some producers started the hashtag #PAY THE PRODUCER, meaning they wanted the artistes to pay them for recordings. This battle started as a back room fight until it spilled into the mainstream news.

Artistes thought they were giving value to the producer by featuring on the riddims and in return producers would market it using the involvement of big artistes to lure more paying rising musicians. Without the big names, the riddims would only feature budding artistes and they would not have weight when released.

Learn or perish

What was once the backbone of the genre and the pinnacle of the culture started becoming a monotonous and rushed sound projects attracting criticism from all angles. Chord progression of ECGD on almost all the riddims and again this was the sound of that era people called in for change as producers were challenged to evolve the sound from “zvigubhu” to a more Afro/pop sound which was becoming the most sought out sound in Africa.

When the “gatekeepers” heard of this they took it as a dig to their egos and the sound. “How can they tell us to change? This is the original sound people identify us with as “voestoes” we don't change for anyone,” this was the producers’ sentiments. From a genre that used Jamaican downloaded riddims, it evolved to a sound that had a Zimbabwean identity, certainly a producer would not have been hurt by a small change in sound to suit the trends and lure more audience that was now becoming loyal to Afrobeats.

Roadmap, what's next and who is next?

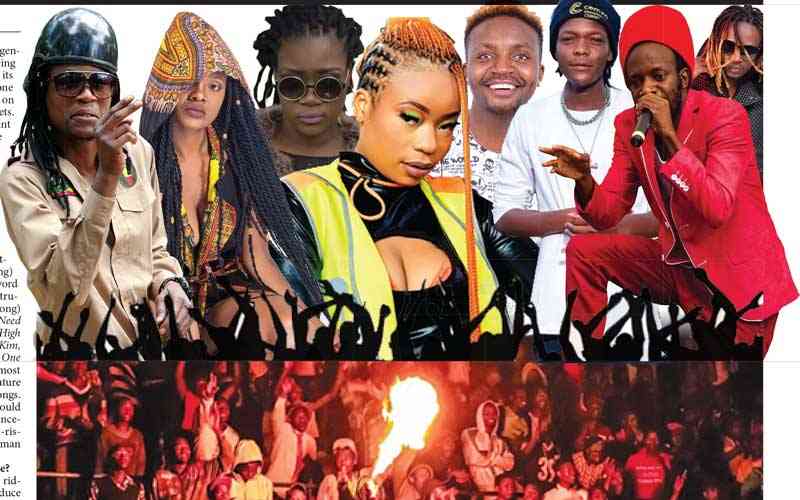

With the number and quality of up-and-coming artistes depreciating by each production, a major decline is being witnessed from the factory that gave rise to artistes of the calibre of Tocky Vibes, Seh Calaz, the late Soul Jah Love, Killer T, Kinnah, Qonfused, Terminator, Celscius, Enzo Ishall, Bazooka, Poptain, Blot, Silent Killer and Kadijah, among others.

Also, prominent female Zimdancehall artistes like Lady Squanda, Bounty Lisa, Lipsy and Lady B were crucial to the growth of the genre and featured on most of these riddims.

These are the artistes that went out of their way to make quality productions and become household names along the way.

It has been years before witnessing new talent that comes through the ranks. Is it because of lack of support from bigger artistes and established producers?

Do established Zimdancehall artistes now need to adopt the riddim culture again? Do they need to take part so that the rising artistes can also get a platform where they can be listened to?

Maybe any riddim now with the likes of Killer T, Seh Calaz, Master H, Blot, Enzo Ishall, Poptain and Kinnah, among others, can give young aspiring artistes a platform they possibly need. Producers need to move with trends, evolve their sound and the sooner they notice the better they navigate?

Need for collaborations

There is a need for collaborations be it features or medleys. People now watch and marvel at the new school of hip-hop artistes who put works together. Seven big names can record one song as they did on Fire Emoji and Gore, among other tracks.

One just wonders how they are doing it as some of them are reportedly in hate relations, but they put work before anything. Imagine how music is travelling so fast via the internet and other social media platforms these days that a medley featuring some big artistes can certainly get more hits.

This is 2024, artistes must stop fighting and work together. The commanding of huge attendances at live concerts both locally and internationally shows that people can still consume the music on a bigger scale if well packaged. It is just a matter of putting egos aside and strategies.