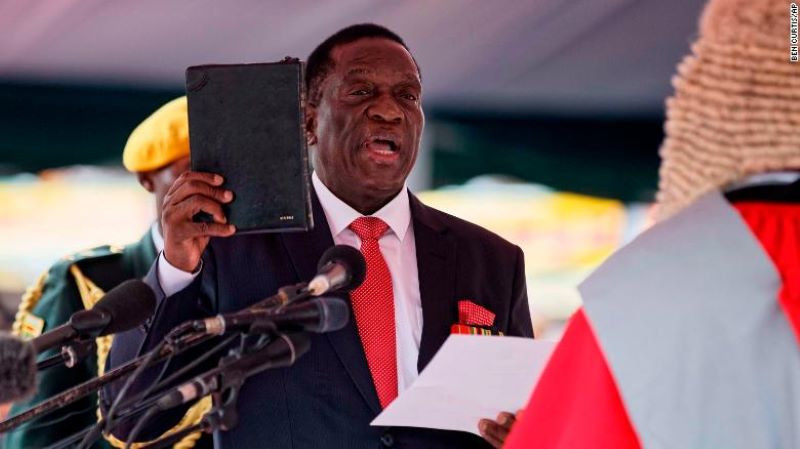

VETERAN politician and former guerrilla war combatant, Emmerson Mnangagwa is today taking an oath to lead Zimbabwe for a second term after being declared winner of the August 23 and 24 harmonised elections.

His inauguration comes hard on the heels of spirited disputation from the main opposition Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC) that the poll results were birthed from a flawed process led by the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission.

In the meantime, thousands of Zimbabweans have petitioned the Sadc Organ on Politics, Defence and Security after regional and international observers roundly described the country’s elections as having failed to meet minimum local, regional and global standards.

The petitioners are calling for “the establishment of an Eminent Persons Group, tasked with negotiating the establishment of a transitional government, composed of political parties and other major citizen groupings”.

According to section 93 of Zimbabwe’s Constitution, “any aggrieved candidate” has the right to challenge the presidential vote at the Constitutional Court within seven days of the declaration of the election results.

Granted, seven days have since passed without CCC leader Nelson Chamisa filing his challenge to Mnangagwa, which lawfully means Mnangagwa can be sworn in as the country’s next President.

What has drawn the ire of neutrals is that invitations for today’s inauguration were sent out before the expiry of the seven-day window.

As much as Mnangagwa and his ruling Zanu PF party may want to haughtily dismiss the political rumblings as a passing fad, they, however, have far-reaching implications.

We state today that these simmering ructions have the potential to adversely affect the country’s socio-economic situation, which, unfortunately, has not been looking good for quite some time now.

If truth be told, Mnangagwa’s first term was anything, but rosy and his second term has little promise given the ongoing grumblings.

While some may want us to believe that the country is firmly on the road to prosperity, facts on the ground point to the opposite. Mnangagwa cannot afford to enter his next term when his win is being hotly contested as that will spook investment which the country desperately needs.

These rumblings cannot be brushed aside or wished away; neither can they be silenced by threats of imprisonment of those opposing Mnangagwa’s rule because this does not augur well for the country’s economic prospects, especially given that Zimbabwe went to the polls riddled with the world’s highest inflation, a seriously weakened local currency, unsustainable domestic and foreign debts and icy global relations, among a host of challenges.

We do not believe that throwing caution to the wind on this issue will help the country to progress in any way, even if many countries may be prepared to support Mnangagwa’s rule.

To legitimise his rule, all Mnangagwa and his party needed to do was to simply wait for the seven-day window to give room for those disputing the results to file court applications.

In 2018, the courts cleared a similar dispute he had with the same rival, and we are puzzled why this time around he could not wait any day longer. We are of the view that there was no need to rush the process as a Swahili proverb states, “hurry hurry has no blessings”.