Tafara Mtutu Research Analyst The year 2021 was a record year for Special-Purpose Acquisition Companies (Spacs) after a whopping 163 Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) were completed at an average IPO size of US$265,2 million. Over US$160 billion was raised through Spacs in the United States, taking the total market cap of all Spacs well above US$800 billion. Spacs are unique entities that are created with the purpose of raising capital on a public exchange to acquire a private business. It is not surprising that activity peaked in 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic because of depressed valuations in many businesses globally that were subsequently ripe for acquisition by Spacs. There are some parallels that one can draw when they compare the mechanics of Spacs to a traditional IPO, but there are some differences that we will explore below.

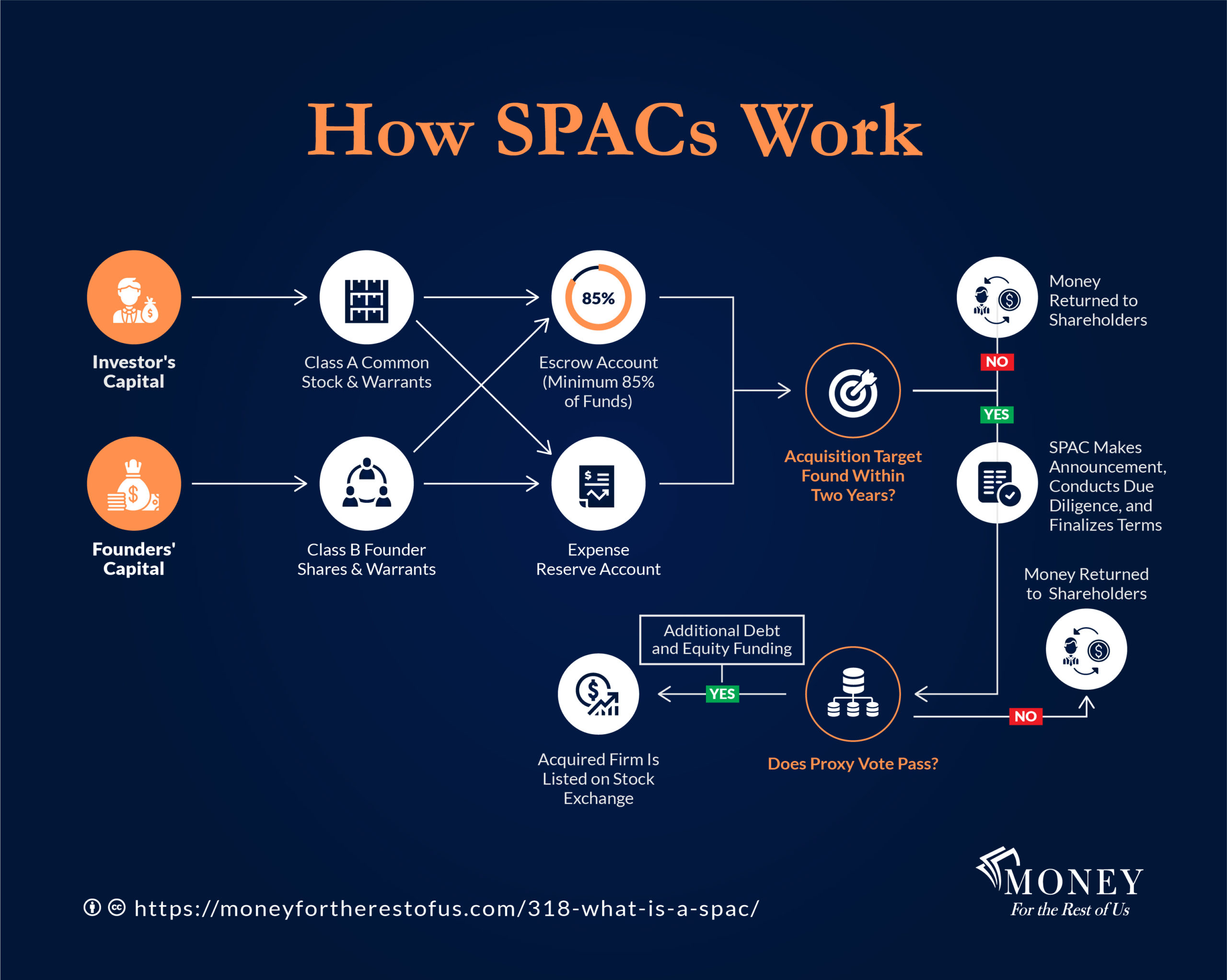

A Spac is also known as a “blank check” company because, while their mandate is to acquire a private business with raised capital, they do not disclose details of companies that the Spac intends to acquire. At the time of listing, Spac shares have no claim to an underlying business, rather only a claim on a business that will be acquired by the capital raised. After the funds have been raised, a search for an appropriate target company begins and negotiations take off the ground. If shareholders vote against a tabled target company, the cycle of a target search repeats until a suitable target company is found and approved by investors. This process is often within a stipulated time frame of two years from the time of the Spac listing and, in the case that no suitable target company is found for the duration of this period, the funds raised are returned to investors. If a target company is found and approved, and all regulatory matters are addressed, the Spac merger will close and the target business becomes a publicly listed entity. A Spac can acquire multiple businesses, but the process becomes considerably more complicated.

The returns for Spac investors have not been appetising compared to traditional equities investments, however. According to Spac Insider, the universe of Spacs seeking a target had a median annualised rate of return (ARR) of -1,6% as of February 18, 2022, while Spacs that announced an acquisition had a median ARR of 1%. When combined, the Spacs universe currently has a median ARR of 0,9% in 2022, which is similar to its 2021 median ARR and 20 basis points below its 2020 median return of 1,1%. In comparison, the S&P 500 gained 26,9%, the Dow Jones Industrial Average gained 18,7% in 2021, and the Nasdaq Composite gained 21,4% in 2021. Spacs are expected to report subdued performance in 2022, however, as waning coronavirus-related risks curtail the fire sale of private companies.

Spacs offer retail investors, who are typically side-lined in the traditional IPO process, early access to new listings. This relatively quicker way of raising capital is also a key advantage during a crisis when most businesses are significantly undervalued and temporarily crippled by exogenous shocks. During such periods, most companies are distressed and some file for insolvency, and owners of these companies disinvest at significant discounts in a fire sale. In addition, Spac sponsors typically pay lower fees compared to traditional IPO fees. However, Spac investors bear the brunt of a fee-of-sorts called the “promote”. The “promote” is a portion of the target company that is given to the Spac manager upon successfully acquiring a target company. This is usually 20% of the shares of the target company purchased by the Spac and it is paid using investor funds. One reason for this promote is to address the misalignment of goals between the investor and the Spac manager. This stems from the conflict of interest that a Spac manager faces without the promote. In such instances, the manager receives fees for managing the SPAC regardless of whether the target company is the best fit for investors or not. Another disadvantage of Spacs is that, while some view them as a separate asset class, they offer superficial diversification benefits as they are highly correlated with traditional equity, both before and after the acquisition of the target company.

Africa is yet to see a Spac listing on one of its 29 exchanges. The closest that Spac have ever been to Africa is through three Spacs that were listed in 2021 on the New York Stock Exchange (African Gold Acquisition Corp and Capitalworks Emerging Acquisition Corp) and NASDAQ (TB SA Acquisition Corp) with a focus on Africa. Unlike the conventional Spacs with a single target, these are driven by investment themes such as mining opportunities, businesses that promote ESG principles, or high growth companies. In Zimbabwe, the possibility of a Spac is something that is elusive, at least in the short- to medium-term. The country’s local capital markets have been extensively affected by local macroeconomics and heightened local risks. For example, if a Spac raised capital in ZW$ on the ZSE, it would be considerably exposed to inflation and currency risk during the process of finding and acquiring a target. In addition, there are few private businesses, if any, in the country that are established and willing to be the target of Spacs. However, we note the active strategy to make Zimbabwe’s stock markets at par with international stock. Since the beginning of 2021, local capital markets have welcomed a new financial instrument — Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) — with a total market cap of ZW$$2,6 billion on the ZSE as of February 22, as well as a commodities exchange, Zimbabwe Mercantile Exchange. In addition, the ZSE has Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) in the pipeline, and this is expected to further deepen Zimbabwe’s capital markets.

- Mtutu is a research analyst at Morgan & Co. — tafara@morganzim.com or +263 774 795 854.