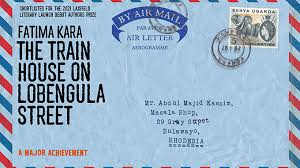

Fatima Kara’s novel, The Train House on Lobengula Street is a rare story about Indians coming to settle in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

It is a carefully crafted story about sojourning and transitioning. You are stunned that such a mature piece of work is only a debut attempt.

This is also a family novel because the sojourner is still within a part of her family. She cannot necessarily renew herself totally or remain stagnant because there is always family to consider. If you run, they stop you. If you linger, they push you on.

Meanwhile the sojourner’s traditions and beliefs are put to an acid test at the same time by three entities: family, time and the new space. This is a novel about continuity and change. Water and fire are in the same mouth.

On the surface, this is the easy-going story about the Kassims; a traditional Indian Muslim family taking the economic opportunities that Southern Rhodesia offers to migrants from the east in the challenging 1950’s and 60’s.

The author does well to weave a solid narrative that constantly persuades the reader to slow down and linger. Sometimes you stop to cross reference details.

This is something you find in other compact novels such as Doris Lessing’s The Grass is Singing and Spiwe Mahachi’s Footprints in the Mists of Time; two novels also about the trials and tribulations of newcomers to Rhodesia.

This novel gradually opens up like a wild and magical onion. The more you read the more you are paid. It is a story in which the least expected is always waiting by the corner.

This is a detective novel of sorts too; working out from 1969 backwards to 1940, up until 1969 once more, in order to establish why and how Razaak grows to become unsympathetic to his wife. You find Razaak sending his daughters far away to Uganda to arranged marriages. He is so determined to scatter his family while hiding behind tradition.

The case of an emaciated Zora, running away from a failed marriage in Uganda, back to Bulawayo with her sympathetic mother, to be asked by her father to go back to Uganda, is quite startling. Zora’s sisters are also unhappy, and they feel like slaves sold down the river. This is a very sensitive story about a long-standing custom that has sustained generations. The author shows without preaching.

The story spins in time, meticulously finding out how tradition and culture turn a once sweet man like Razaak into a scoundrel and a hater of his wife who is a woman who gives Razaak eight children without complaining.

Razaak gradually becomes cold towards a woman whose life is spent being routinely pregnant; calling on the nurse and the elders to help with her deliveries.

What will a newly arrived and newly married young Gujarati woman in colonial Bulawayo of the 1960’s want from her people and the colonial government?

That is complicated. Kulsum comes to Bulawayo just after marrying Razaak in India and they settle in the broad Kassim family, led by a laid-back patriarch called Abaa.

Virtually a villager from Hunyana village in India, Kulsum is caught up in a struggle against both Indian Muslim traditions and the racist terrain of Southern Rhodesia. She is in a double bind. Once outside the bustle of the train station in Bulawayo on her first day, Kulsum is fascinated to see that there are no rickshawallahs here, no loud vegetable sellers, no children playing, no beggars, no goats and no cows too!

While she is still working out her new geographical location, Kulsum senses that Razaak is more inclined to forget her! As soon as Razaak sees his long-lost father, his wife becomes second fiddle.

When father and son hug and exclaim at the station, it is left to the black servant, Jabulani, to smile at poor Kulsum and ask her to join the celebrating party in the car. The marriage and attachment between Razaak and Kulsum end as soon as Razaak meets his father!

Even when they get home, Kulsum becomes an invisible woman, and her opportunistic mother-in-law quickly takes over, more or less like an irate prison warder.

When Kulsum meets her mother-in-law, Jee Ma, she does not even ask after Kulsum’s sisters nor offer condolences on the death of Kulsum’s mother. Jee Ma becomes Kulsum’s competitor with an upper hand. That Abaa says Kulsum cooks better than Jee Ma makes it worse!

Soon Kulsum gives birth to a boy when Jee Ma has no son to boast about! You are given opportunity to see how some women treat fellow women in the race to please men.

Then one day Abaa fumbles with her daughter in law wanting intimacy. This horrifies Kulsum who cannot report. She wonders if it is because she struggles to secure her scarf, the laj. Jee Maa overworks Kulsum like a donkey even when she is going through many of her pregnancies. The malicious backbiting continues until Kulsum and Razaak move out of Abaa’s place in the middle of the night to find refuge amongst other Indians in the vicinity.

Meanwhile the nationalist movement is growing in Rhodesia and the Indians realize that they are only tolerated as a white man’s buffer against the black people. Fortunately, there are the politically conscious people such as Amar. There is the radical coloured woman, the nurse, who is dragging the Indian community to take their resistance. There is Lakshmi, the Hindu neighbour, who realises that people had better quickly grow and transcend tradition.

Kulsum has to deal with her own in-built contradictions. She constantly feels that although her in laws ill-treat her, she has a right to their love. She fights hard to embrace those who reject her until the option is to move on. This is consistent with the question she is asked by Nurse: “So, tell me, which place did you like living in best; in Hunyana, your ancestral village, or Madagascar, where you sold fish, or here, where your husband sells spices?”

And Kulsum's newly minted answer is: “This place.”

Razaak appears radical at first, taking on his family when he is wronged and even asking to leave in protest with his wife children in the middle of the night. But as soon as his wife proves to be more enterprising and conscientious than him, Razaak starts to want to fall back on tradition. He hates the house that his wife builds for the family on Lobengula Street because, as many say, it looks like a train house! But the truth is that they now have a house of sorts.

At one point Razaak cries out: “I am the father and I decide (for my daughters). We will court trouble if we do not follow tradition.” He feels defeated by his wife and falls back on the extended family which has all along looked down upon him. In chapter 17, which is the climax for me, Razaak spills the beans pitifully: “I don’t have the courage. Abaa was right about sticking to tradition. You, Nurse, my wife-you are all moving too fast for me.”

While this is a rare story about the lives of Indians in Zimbabwe, sadly the Africans are totally behind the scenes, only coming in as houseboys. Jabulani, for instance is rather unexplored. He is seen but is not heard.

Asked by Asjad Nazir of the EasternEye on what inspired her to write this novel, Fatima Kara says, “During my childhood in Bulawayo’s vibrant Indian community, I saw a lot of things that troubled me — like young women travelling to faraway places to enter arranged marriages and Indian men practicing civil disobedience against the white police. I couldn’t know for sure what happened to them all, but I wanted to write a version of their stories.”

On Amazon it is indicated that Fatima Kara is a Zimbabwean writer living in the USA and that the author has an MFA from Spalding University in Kentucky. When not writing, she propagates fruit and nut trees, and plants them in schools and rural communities around Zimbabwe.

The Train House on Lobengula Street was shortlisted for the UK’s Laxfield Literary Launch Prize in 2020. The book can be ordered through: Amazon.com: The Train House on Lobengula Street: 9781915023094: Kara, Fatima: Books