My submission this week veers too close to the conversation of opposition party structures. Frankly, that is a convoluted discourse, which I would rather not get entangled in.

If this is any assurance, the pursuit of my missive is not to talk about the existence or non-existence of structures, nor the wisdom of having them or lack of it. I also do not intend to talk about what structure to have when or where. Quite to the contrary, I intend to talk about a structure that opposition parties should not have. The province.

The most immediate task of an opposition party

Any opposition party worth its name and is serious about acquisition of state power through elections must necessarily invest in party organising and voter mobilisation.

This can be around ideology, democratic processes, response to issues, party programme or electioneering. My problem with the province emanates from this framing.

Party organising and voter mobilisation is a business that falls within the ambit of political geography. It is about how space, place, and politics interact to create, forge, transform, and distribute power.

In other words, spatial considerations in the formation of party structures are laden with power relations! Structures are not just organisational; they are also geographic and it is this interaction of organisation and geography that influences electoral outcomes of parties.

So, party structures are a geographic expression of social and political power. That is what we mean by political geography.

- Record breaker Mpofu revisits difficult upbringing

- Mino Raiola: Football agent dies aged 54

- ED speaks on prices, exchange rate

- Mapeza looks forward to Bosso challenge

Keep Reading

But what has that got to do with my outrageous antipathy with the province?

Mobilising the individual man/woman

The endeavour of political organising is to mobilise the individual man or woman. It is a local and very grassroots mission. It, therefore, falls within the purview of local structures to carry out this important task.

Provinces cannot do so because they are superficial and have no ground to speak of. They, on the other hand, are more preoccupied with the aggregation of diverse issues and considerations to present a ‘united position’ of the province.

What this means dear reader, is that some person seated in some office somewhere at the Matabeleland South provincial office in Gwanda (which ironically is physically located in a district) decides what is important for Madlambudzi and Vhembe without having a clue or a connection to these places.

And when what is important for the different locales has no convergence, the province arrogates itself the power to decide what to throw into a trash compartment labelled ‘compromise.’ Trade-offs, horse trading and patronage ensue.

This is all in the name of achieving ‘consensus’ and presenting a common position from the province.

Nothing common about our provinces!

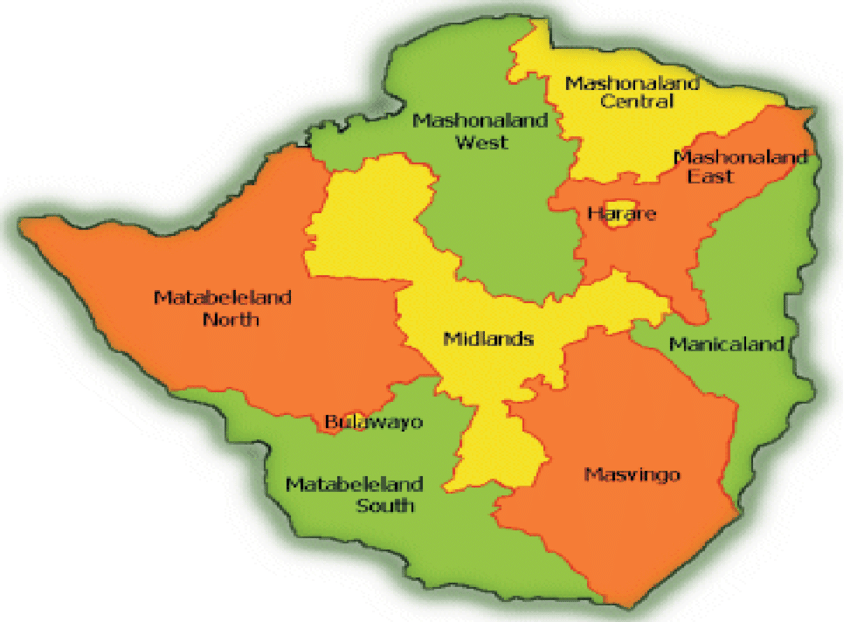

Achieving a truly meaningful and common provincial position is difficult as provincial boundaries in Zimbabwe are based on topographic considerations, and logistical and administrative convenience.

This is without any consideration for shared identity, interests, or circumstances. The quest to aggregate the province as a unit trivialises some strong local sentiments.

And like all aggregation results in disenfranchisement of some parts of the population. The closest that these interests can converge is at the district/constituency level.

The province only serves the state!

Opposition parties must understand that there is no place called ‘province’. The province is an abstract and superficial, if not mythical location, which in political geography, is only useful to the government and by implication to the ruling party.

Provinces are a construct of the state, in fact, they are a relic of the colonial political geography of the Rhodesian state. The purpose of the province was – and still is to help the state to administer its business, maintain order, and to ‘group and manage’ diverse communities for the purposes of consolidating power and social control. Opposition parties have no such need for the province.

Form follows function

Is it not age-old wisdom that the form of any organisation must be based on function? I understand that wisdom visits us not all at once but is discriminatory.

Some people never suffer the inconvenience of wisdom’s visit. Abandlwane abathungululi kanye kanye/vana vembwa havasvinure pamwe chete (puppies do not gain sight at the same time).

What am I driving at?

The highest unit for political organising for opposition parties is the constituency or district with the national structure being for political administration. I, however, understand the follow-fashion architecture of opposition to mirror the ruling party and the state.

It is the pitfall of social reproduction where all other enterprises model themselves along dominant forces in society. With this thinking, what purpose does the province serve for parties without state power?

None!

The opposition has no business having a provincial structure. And that is precisely the reason why the province becomes a power for itself because it has no direct constituency.

A power for itself!

Because it has no constituency and certainly no power of its own, party provincial structure is a power not unto itself but for itself.

On one hand, it serves the whims of the ‘central’ to stranglehold the ‘local.’

When it feels threatened from below, it becomes the proverbial emissary from above (the 'central').

On the other hand, threatened from above, it appropriates the ‘local’ and wields it as a weapon against the central. It becomes a messenger of the people, a godfather of the local.

The proverbial bat of politics

The province is a liminal structure that is confused about whether it represents the interests of the central or those of the local. In its confusion, it ends up representing its own interests — which by the way are not anchored on any constituency since they have none.

It wields authority but has no power or legitimacy.

Its power is always borrowed or claimed either from the top or from the bottom. It operates in an amphibious fashion, weaponising the central to deal with the local and shifting to weaponise the local to deal with the central as its own interests and whims dictate.

It is a treacherous structure that swings like a pendulum depending on where power resides at a particular moment. The province is the proverbial bat of politics. It is not clear whether it is a bird or a rodent!

The perfidious nature of a provincial structure is that it can evade responsibility and accountability while claiming credit – and benefits of the political enterprise!

While political structures depersonalise power, the province, because of its lack of direct constituency nor responsibility and accountability is fertile ground on which personalisation of power festers.

It is ineffective and a place where patronage is most rampant.

This partly explains why it is easier for powermongers to emerge as political ‘godfathers’, and ‘heavyweights’ at the provincial level than at national level.

One cannot be a godfather in a district because there is direct control of the behaviour of leaders by the constituents.

They also cannot be a godfather at national level because there is collective excising of power, responsibility, and accountability at that level.

Can someone make it make sense?

Provincial structures have primarily been framed by the governing elite for administrative purposes but has also been used for political control. It only makes sense for the state and the ruling elite.

From them, it is not only convenient but indispensable.

The political geography of the province can never make sense outside the purview of the state! It is more of a liability than an asset. It does not add any political value to the business of political parties without state power.

There has never been a compelling and coherent argument on why there should be another level between the local and the national for an opposition party in a small country like ours. As such, the province adds no tangible value to the opposition political enterprise.

As such the province must be abolished!

The abolishing of provincial structures by opposition parties can potentially help strengthen local politics by adding quality leadership at the local level who would otherwise be parked in a useless, powerless deadwood provincial tier that serves no one but itself!

The sober view

Opposition parties that are serious about mass mobilisation must understand political geography.

They must understand that outside of state power, the province is perfidious deadwood, which is both a liability and unnecessary burden.

Effective political organisation and mobilisation for opposition parties, who do not enjoy proximity to state power must necessarily be pursued by first dismantling the so-called ‘provincial structure’. It is a treacherous deadweight that no party without state power must have.

This is my sober view. I take no prisoners!

- Dumani is an independent political analyst. He writes in his personal capacity. Twitter - @NtandoDumani