African countries must find a way of fighting anti-microbial resistance (AMR) in the healthcare system to avoid unnecessary deaths.

A few months ago, Ghana Public Health Association president Amofah George narrated how he saw a patient die after failing to respond to all the available antibiotics used for managing her septicemic condition, blood poisoning, especially caused by bacteria or their toxins.

He attributed the situation to antibiotic resistance, or AMR which he said has become a growing pandemic.

The problem is simple: Africa’s healthcare system does not routinely rely on laboratories to produce tests for treatment. AMR programme manager of the African Society for Laboratory Medicine (ASLM), Edwin Shumba, told IPS: “Ghana, like other countries on the continent, rely on a few medical laboratories to conduct bacteriology testing as part of the routine clinical services.”

“This means that doctors are flying blind when prescribing a treatment to their patients, and public health experts do not have an insight of what is ongoing in terms of AMR, at hospital and national level,” Shumba said.

“The growing threat of AMR has implications for patient care: the antibiotics that used to work will not be able to cure the infections caused by resistant bacteria anymore. This means more that infections might take longer to cure, might be more severe (mortality, morbidity), and will cost more to the society.”

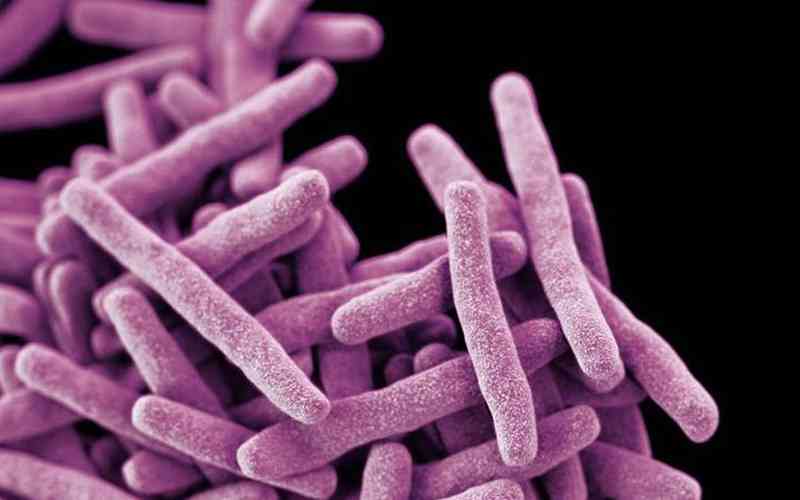

Worried by the increasing cases of AMR, ASLM has spearheaded a study, and data from 14 sub-Saharan countries show that only five out of the 15 antibiotic-resistant pathogens — a bacterium, virus, or other microorganisms that can cause disease — designated by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as a priority are being consistently tested, and that all five demonstrated high resistance.

Across the 14 countries, clinical and treatment data are not being linked to laboratory results, making it hard to understand what’s driving AMR.

- Africa hit hard by high e-waste pollution

- Africa is paying dearly for the Russian/Ukraine conflict

- Pathways for repurposing resources are long overdue in developing countries

- Poor co-ordination makes it difficult to see where African food systems are going

Keep Reading

Out of almost 187 000 samples tested for AMR, around 88% had no information on patients’ clinical profile, including diagnosis/origin of infection, presence of indwelling devices (such as urinary catheters, feeding tubes, and wound drains) often associated with development of healthcare-associated infection, comorbidities, or antimicrobial usage. The remaining 12% had incomplete information.

The multi-year, multi-country study was carried out by the Mapping Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial use Partnership (MAAP), a consortium spearheaded by ASLM, with partners including the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), the One Health Trust, the West African Health Organisation (WAHO), the East, Central, and Southern Africa Health Community, Innovative Support to Emergencies, Diseases, and Disasters, and IQVIA.

It provides stark insights into the under-reported depth of the AMR crisis across Africa and lays out urgent policy recommendations to address the emergency.

MAAP reviewed 819 584 AMR records from 2016 to 2019 from 205 laboratories across Burkina Faso, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi, eSwatini, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Gabon, and Cameroon. MAAP also reviewed data from 327 hospital and community pharmacies and 16 national-level AMC datasets.

The researchers found that most African laboratories are not ready for AMR testing. Only 1,3% of the 50 000 medical laboratories forming the laboratory networks of the 14 participating countries conduct bacteriology testing. And of those, only a fraction can handle the scientific processes needed to evaluate AMR.

Researchers also found that in eight of the 14 countries, more than half of the population is out of reach of any bacteriology laboratory.

The study results provide insights into the AMR burden and antimicrobial consumption in the 14 countries where most available AMR data is based only on statistical modelling. The effort by MAAP is the first of its kind to systematically collect, process, and evaluate large quantities of AMR and antimicrobial consumption (AMC) data in Africa.

The WHO has repeatedly stated that AMR is a global health priority — and is, in fact, one of the leading public health threats of the 21st century. A recent study estimated that, in 2019, nearly 1,3 million deaths globally were attributed to antimicrobial-resistant bacterial infections. Africa was found to have the highest mortality rate from AMR infections in the world, with 24 deaths per 100 000 attributable to AMR.

ASLM’s director of science and new initiatives, Pascale Ondoa, said: “Africa is struggling to fight drug-resistant pathogens, just like the rest of the world, but our struggle is compounded by the fact that we don’t have an accurate picture of how antimicrobial resistance is impacting our citizens and health systems.”

The research also found that only four drugs comprised more than two-thirds (67%) of all the antibiotics used in healthcare settings. Stronger medicines to treat more resistant infections (such as severe pneumonia, sepsis, and complicated intra-abdominal infections) were unavailable, suggesting limited access to some groups of antibiotics.

ASLM chief executive Nqobile Ndlovu said: “Across Africa, even where data on antimicrobial resistance is collected, it is not always accessible, often recorded by hand, and rarely consolidated or shared with policymakers; as a result, health experts are flying blind and cannot develop and deploy policies that would limit or curtail antimicrobial resistance.”

“The disconnect between patient data and antimicrobial resistance results, coupled with the extreme antimicrobial resistance burden, makes it incredibly difficult to provide accurate guidelines for patient care and wider public health policies,” said Yewande Alimi, Africa CDC AMR programme co-ordinator.

“Hence, collecting and connecting laboratory, pharmacy, and clinical data will be essential to provide a baseline and a reference for public health actions.”

Said IQVIA’s head of Public Health (Africa and Middle East) and Real-World Evidence (Middle East), Deepak Batra: “Collectively, the data highlights a dual problem of limited access to antibiotics and irrational use of those that are available.

“As a result, people don’t get the right treatment for severe infections, and irrational use of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance for existing available treatment options. Routine monitoring of antimicrobial consumption could help monitor the limited access and irrational use.”

Based on the findings, MAAP calls for a drastic increase in the quality and quantity of AMR and AMC data being collected across the continent, along with revised AMR control strategies and research priorities.

For Shumba, Ghana, like the rest of Africa, can fight AMR by including critical interventions in revised versions of the national AMR Action plans, essential medicine Lists, laboratory strategies, and standard treatment guidelines.

“This heavy toll on the health systems poses a major threat to progress made in health and in the attainment of Universal Health Coverage, the African Union’s Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals,” he added.

Shumba said the AMR co-ordinating committee of Ghana could assist other policymakers in using the evidence gathered by the MAAP project to refine their strategies for AMR containment. In addition, they can plan to increase the number and capacity of medical laboratories to conduct bacteriology testing in the country.