THE ambers of democracy ignited by the post-Cold War, and post-liberation politics and aspirations have died down. On their lukewarm ashes has been the birth of incessant coups in Africa, a rise in strongmen politics, and, elsewhere in the world, the rise of populist authoritarianism, and far-right parties.

For democrats all over the world, this is a serious concern as it indicts the legitimacy of democracy as the best form of government.

Some pessimists have gone on to declare that democracy is dead or dying. But, that is not entirely true. It is a pathological and self-serving declaration of death-on-arrival by cynics, who need an excuse to defer to their inclinations that are otherwise anathema to democracy.

Too early for obituaries, epitaphs

Democracy as a form of government is not perfect. Even Winston Churchill once quipped, “democracy is the worst form of government — except for all the others that have been tried”.

Like all politics, it has its own moments of madness, yet it is still the most popular proposition which people yearn for. Most importantly, it is the fairest and most just.

To suggest that modern democracy in Africa, which is less than 40 years old in most countries, is dead is akin to declaring it dead on arrival.

Unlike other more established democracies with centuries-old democratic traditions in the United States and Europe, democracy in its broad and contemporary sense is still a very nascent proposition in Africa.

- Globalisation under threat: The more things change, the more they remain the same

- The sober view: Democracy in Africa needs new tools

Keep Reading

The converging crises of climate change, health pandemics, and violent conflicts exert pressure and amplify the inadequacies of fragile global economic structures.

While these crises expose the fallacy of the “invisible hand” which epitomises the age-old inadequacies of capitalism, they get to be blamed on democracy. This shakes most people’s belief and faith in democracy.

If it is any assurance dear reader, there is an encouraging pocket of defiance. Amid the adversities, as an Afrobarometer survey in 2016 found, the majority of Africans still believe in democracy and are willing to fight for it.

To do that, they need new tools. The current democracy toolbox is depleted and has only one decrepit hammer whose handle sooner bruises the carpenter’s palms than drives the proverbial nail into the wood.

Be that as it may, it is too early for obituaries and epitaphs. Let the undertaker enjoy his sleep for now. Of course, we cannot ignore the reality that the legitimacy of democracy has been questioned - and found wanting.

Here is why.

Morbid hypocrisy

Some champions of democracy in the stock of the US, United Kingdom and France suffer from morbid hypocrisy, which is a danger to the legitimacy of democracy everywhere else.

In one breath, they subject their domestic policies to the principles and values of democracy. They even accord equal rights and liberties and “concede equal citizenship …to the leopard and the lion, the elephant and the springbok, the hyena, the black mamba and the pestilential mosquito”, to quote Thabo Mbeki’s musings in his seminal speech titled I am an African.

Fair and good.

But, in the same breath, the mentioned democracies incessantly throw out the same democratic principles and values at the altar of expediency on international matters, as their own caprices, geopolitical interests, and economic conveniences dictate.

The post-9/11 war on terror is a prime example, the wheeling and dealing with known autocrats is well documented, military invasions are constant grief, and unfair trade practices are pervasive.

Coming from some countries in the global north, which have always been seen as the doyen of democracy, these practices erode the legitimacy of democracy.

Practicing and wannabe autocrats are quick to point to this poisoned chalice and refuse to drink from it. They appropriate the fallacy of appealing to hypocrisy, and they get away with it.

Interventionism rarely works

While some Western countries have employed tools that lift and support democratisation, others have opted for the hammer to demand it, and impatiently bludgeon everyone into submission.

This is without regard to the reality that democracy needs time to take root. It is not an event, but an incremental process of making gains and consolidating them. And, the problems of democracy are not just nails, they are diverse and need a variety of tools.

Some of these hammers have taken the form of interventionist measures imposed by international financial institutions, economic sanctions, military invasions, supporting uprisings, mass protests, and in the extreme — regime change.

It has resulted in democracy being viewed not as a legitimate demand by citizens, but as a Trojan horse weaponised by the West for regime change.

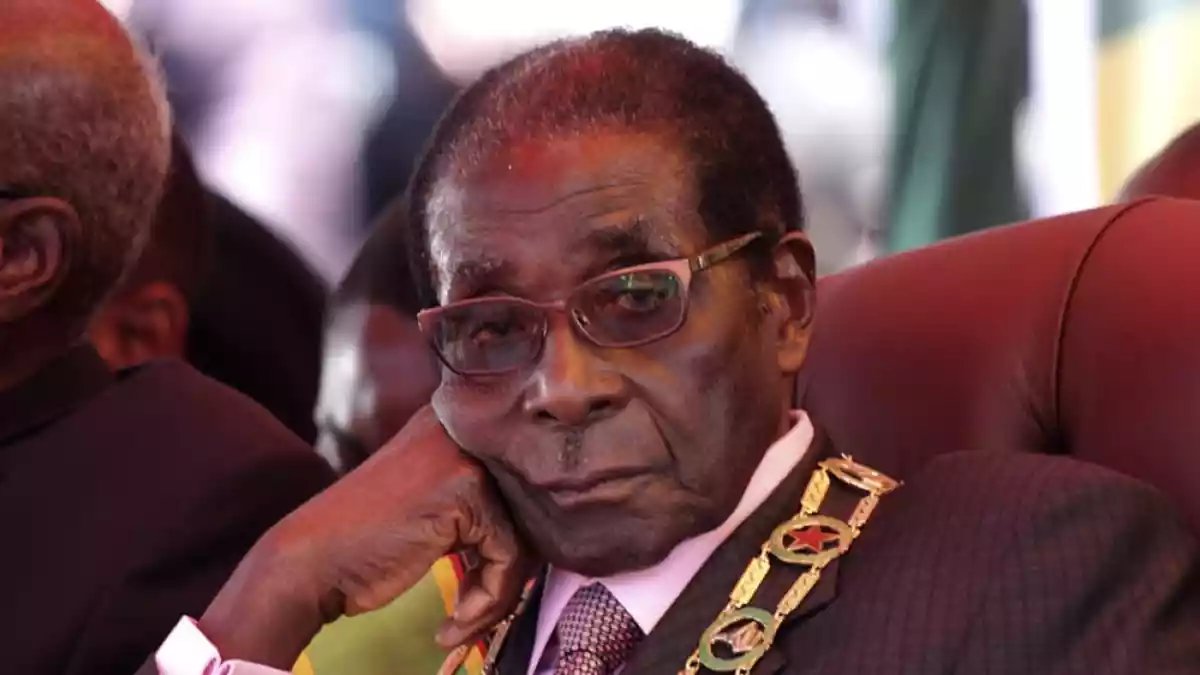

For crude autocrats, it only serves to strengthen their resolve in the name of defending their sovereignty. The late former Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe was a champion of such. It gives them an excuse for their domestic failures and a justification to shrink the democratic space further.

Sophisticated ones learn the “language of democracy”, institute minimal reforms, and religiously perform the rituals of democracy like elections without substantive democratic reform.

They weaponise democracy against itself. Thus, they reap the benefits of sounding and appearing democratic without the inconvenience of being. Their democracy is a painted donkey! Painted black and white to resemble a zebra.

But the long ears, the lazy gait, the stubbornness, and constant braying betrays it.

Echo chambers, disconnect

The spaces of democratic discourse have over time largely become echo chambers for the converted. Activists and politicians echo each other’s high-sounding nothing.

Plastic words disconnected from the common language of common people. And the audience for this self-pleasuring nonsense — is themselves! It renders the democracy discourse a preserve for the elite, academics, career activists and politicians.

The progressive movement has always been the agora of robust discourse and debate. Now it has largely become an echo chamber for those who agree, any dissent becomes fodder for cancel culture and its woke policing unit. Quite dismaying for self-anointed democrats!

As if the troubles will not end, the youth and the middle class — wherever it has not yet been decimated by the obscene and unforgivable inequality — have disconnected.

Disconnected from the discourse in which they are a critical voice and a scaffold. All discourses for broad societal and political transformation in the world have always been ignited and anchored by the middle class. This includes the nationalist movement and the democracy movement at the turn of the millennium in Zimbabwe. With this disconnect, democracy is weakened.

Democracy needs new tools

Democracy needs new tools to shape its aspirational proposition. It needs tools that do not result in the unintended harm of eroding its legitimacy but rather, strengthen it.

Democracy must inspire hope; hope that is not naïve, but anchored on legitimate and credible action. We need new tools to demand, support, transform, negotiate and shape democracy. The tools must forge democratic messaging anchored on hope and not despair.

It needs new tools to deliver outcomes emanating from the legitimate expectations of citizens within the ambit of the social contract.

It must deliver public goods and change the material conditions of the masses. There’s a need to understand that people are not concerned about democratic concepts which are abstract to them.

People do not necessarily need to know about all the provisions of the constitution, they do not need to know every section of the bill of rights, we have lawyers for that.

People only need to know that when they have problems, they will get justice. They need to know that the courts will deliver for them.

They need to know that their safety and security is guaranteed. Should they fall sick they will find medical care, and if hungry they will get food.

They need jobs! Decent jobs. It is jobs that deliver dignity, food, and shelter. Jobs deliver access to healthcare and to education. Then democracy will make sense. We need to connect democracy to public goods.

The sober view

Democracy needs institutions that are guardrails to failproof it against external and internal shocks. Institutions that are not, ironically, weaponised against democracy itself. While movements may usher in democracy, it is institutions that safeguard, sustain and deepen it.

Democrats need to tell the story of democracy and keep its memory alive. They must reframe past struggles like the liberation struggle as a struggle for democracy.

It might not have carried the label, but that is exactly what it was about. It was about dignity, equality, fairness, access to public goods, human rights and the sanctity of universal adult suffrage. It is clear that democracy has much older struggles than the recent post-Cold War rush.

At the moment, the story of democracy begins with, “secondly …” When the full story of democracy is told, it must start with, “in the beginning ...”

The new tools of democracy must unclog the channels of engagement and reconnect the middle class, youth and women. The tools must also connect the different struggles like feminism, labour rights, the informal economy, students’ demands and climate change, etc, to democracy.

These are struggles for democracy. Unfortunately, they have largely been disconnected, even from each other, and operate in silos. To scaffold and anchor democracy, the tools must lever on the middle class as a bulwark for broad societal transformation.

In the process, these connections will raise new and credible champions for democracy not just loudmouths. As Friedrich Ebert once asserted, “democracy needs democrats”.

The wisdom of Sir Seretse Khama teaches us that, “Democracy, like a little plant, does not grow or develop on its own. It must be nursed and nurtured if it is to grow and flourish. It must be believed in and practiced if it is to be appreciated. And it must be fought for and defended if it is to survive.”

This is my sober view; I take no prisoners!

Dumani is an independent political analyst. He writes in his personal capacity. — @NtandoDumani.