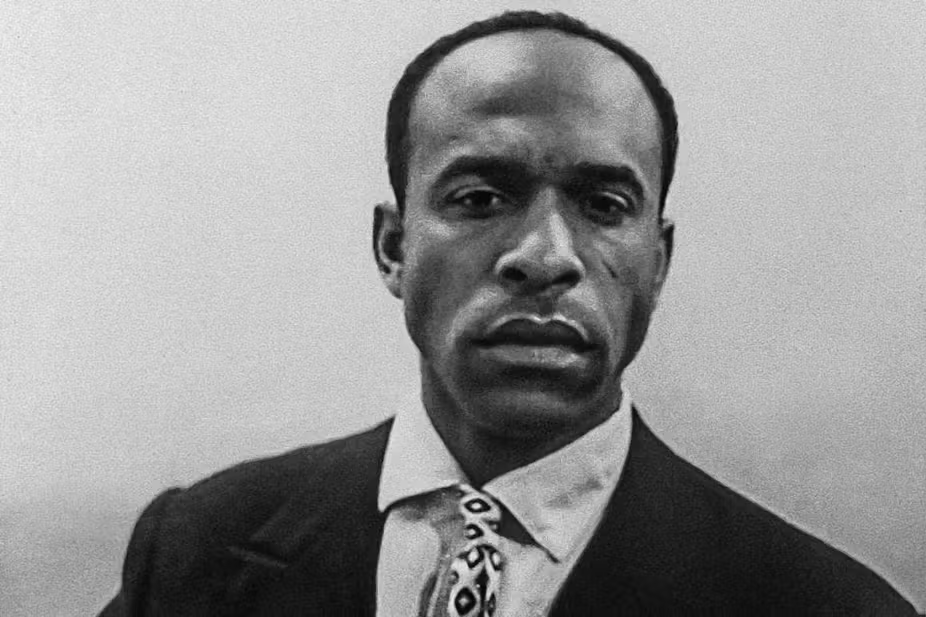

Before I came across Cynthia Marangwanda’s novella, Shards, which was first published in 2014 by A LAN Readers Publication in Zimbabwe, and republished in 2023 by Carnelian Heart Publishing Ltd in the UK, I had always associated the Dambudzo Marechera style and approaches with male writers only.

From my very close experience with students of literature in Zimbabwe, the excitement with Marechera is more pronounced in young men than in women.

The female students tend to find Marechera rather outrageous and frightening, too, because of some of his scenes that are full of violence against women characters. The female students feel that Marechera is “too macho” in his writings and that he does not pay much respect to “women’s sensibilities.”

On pointing out that Marechera’s work is, in fact, protesting against the dehumanisation of women, one of these female students felt that “Marechera protests, right, but he still writes about violence against women the way men do.”

However, Cynthia Marangwanda’s writing in Shards carries close and vigorous stylistic and linquistic echoes of Dambudzo Marechera. Marangwanda’s hypnotic and intense writing style, done in a language laden with abstract and acidic imagery, creates a mood with very close echoes to Marechera.

For example, describing the house servant, Marangwanda’s narrator says, “She casts me a slanted glance, the type a cat would throw a mouse asking for directions…” and later, “she throws me an angular look, the type a crocodile would cast a fisherman standing by the river…”

On describing her first meeting with Pan, the narrator says, “Perception rotated on its axis and tilted abnormally to the side. A revolution was abreast…the moment was shattered into scattering shards…The strange young man’s voice was like scissors…”

When the narrator is locked up in the mental facility, after what her family assumes is a mental breakdown, a Marecherean presence joins her: “As if from nowhere a youthful creature came and sat beside me. His hair was a field of short dark spikes jutting out like upturned nails, his build was awkward, as if his body had tried and failed to wrest itself from the clutches of adolescence, and he wore the most elaborate horn-rimmed glasses I’d laid eyes on. The air he exuded was both manic and moody.”

- Book review: Shards

Keep Reading

This figure she calls Benzi, as he calls her Mupengo. Together they discuss the poetry of Dylan Thomas and Christopher Okigbo.

When you set aside language and style, the Shards story has a lot of other intrigues. It is a story about a sensitive 23-year-old woman from the medium density suburb, relatively comfortable, cosmopolitan and erudite. She is in the midst of rebelling against the nationalist generation of her parents. She vigorously claims that they are failing to instill order in the community and all around them is a life that is bereft of dignity and integrity.

She calls herself a practicing nihilist. She thinks that “life is a gradual succumbing.” When the novel begins, she is clearly against everything and everybody.

She joins two institutions of higher learning as a student, and drops out because, as she says, she finds “formal education to be a sort of death of information.”

She wears tribal print dresses that sweep the floor. She likes township jazz and reggae tunes. She is into black consciousness, reading a lot around the ideas of Marcus Garvey. She is also being courted by an elderly Pan-Africanist filmmaker.

She has tried to kill herself once through self-poisoning but has stopped trying “because of a fear of failing again.”

She has a friend called Pan, a fine art practitioner who lives alone in a flat rented for him by an elderly woman in Russia in exchange of sexual favours whenever she visits.

The first time that the narrator meets Pan, it is love at first sight that jolts her to her roots. “And so we stood there for what seemed an interminable second staring sharply through each other… A revolution was abreast, and its focal point seemed to be an area of grey matter, a lace of blurred lines. The moment was shattered into shards by the voice of the unusual young man.”

Another exciting side to this novel is how the narrator is overwhelmed and haunted by the spirit of her dead grandmother. You may want to think that this is a version of spirit possession. She sees Grandmother and is immobilised by her. The people around her think that she has mental problems.

Grandmother first appears to the narrator six years after her burial when the narrator is having her hair plaited by a talkative hairdresser who is going on and on about the men that she stalks. Listening to the woman’s escapades, the narrator appears to fall asleep and that is when she sees “my buried grandmother standing slightly to the side, in front of me.” The narrator is startled, and the hairdresser is silenced, assuming that the narrator has been stung by an insect.

Grandmother appears “with her hair soaring.” and “she was holding out an ochre coloured wrap cloth” which she is asking her granddaughter to receive. When the narrator does not accept this ritual gift, Grandmother becomes very angry and menacing.

Grandmother eventually flies out through the window!

The girl assumes that this may not take place again and that she has been going through a bout of schizophrenia. But grandmother returns three days later, as the narrator is in her bedroom, surfing the internet! This time Grandmother is holding a wounded white lion cub, but the narrator rejects this gift as well.

Grandmother advances towards the frightened girl as “she bared her decayed fangs, and her eyes began to flash in a manner suited to lightning…”

Sometimes, when the girl is intoxicated with alcohol, Grandmother’s visitations increase. Grandmother appears everywhere and more regularly. She wants the girl to accept something, but the girl is adamant. The duel continues and neither the Christian bible nor the psychologist is able to rescue the young woman.

This story is special in the sense that, to my knowledge, it is the first novel from Zimbabwe to explore the experiences of a character who is going through the early days of manifesting shave (alien spirit) or mudzimu (ancestral spirit).

This is a process called kurwadziswa or kusunyiwa nemweya (the early body and spiritual pains) experienced by a medium (homwe) until the shave or mudzimu are ritually accepted and welcomed.

At this stage the medium may become sick, mentally and physically until the matter resolved. Marangwanda explores this with a postmodern brush, much like what Marechera does in House of Hunger, capturing how the boy in school hears voices and feels like he is being pursued by invisible strangers. However, in Nehanda, Yvonne Vera explores real spirit possession, the experiences of a fully established mudzimu.

The girl soon teams up with various other radicals. There is her former school mate, Sheba. She is “dazzling. Wondrous. Diabolically beautiful.”

Sheba’s parents want her to study Architecture, but Sheba ends up choosing to go to Vienna where she studies Fine Art.

Sheba makes the narrator feel inferior as Sheba is more physically and mentally endowed. She has already tried to commit suicide three times with a razor and dozens of pills.

She says she wants to die in order to escape from what she calls “the agony of a fraudulent existence.” Ironically, suitors flock around her, desperately. But she wants to die. She wants to extinguish herself like a candle.

There is also another radical, a sculptor called Shavi. He is “renowned for his grotesquely exquisite sculptures that hint at macabre areas of the subconscious.” Shavi explains why people of his generation are suicidal: “Alienation is the root of it. A widening remoteness and detachment that refuses to be bridged. One can’t help but fall headlong into the gaping gap…. These are futile times we are living in… I remember the days a handful of us would meet in the park. We were all twenty something, jobless and godless…When one of us surrendered and slit his throat open on a sunny day in full view of our windowless eye, we knew the implosion had begun…”

While they are at it, Pan appears from the gallery where he has been trying to hand in his work.

His news is that: “They said my work doesn’t fit the criteria. What f- criteria? They said it is difficult to categorise, it screams too loud…what in Satan’s bloody hell does that mean?” he bellows.

Soon they all feel futile and helpless, and they go away in search of anything exciting and they come across a demonstrating mob that they all happily join, crashing into cars and buildings until they fall flat. Anything that opposes the establishment is good for this generation.

The major message is that; when you are in a society that does not accept the contributions of your talent and skills, then you are doomed to go round and round the face of the earth.

Meanwhile, Grandmother pursues the narrator. She has many offerings. She will not relent. How will the narrator knock off this intruder from her mind, or will she start to listen to Grandmother? But how can a rebel listen to an elderly woman from beyond? Is a return to tradition and roots the answer to all this angst?

Shards, vacillates between postmodernism and spirit possession. It races on with no calibrated chapters. We turn and turn in the cauldron like the old fisherman in Hemingway’s Oldman and the Sea.

Shards won the National Arts Merit award in 2015, in the Outstanding First Creative Work category. Cynthia Marangwanda is genuinely talented. She is spontaneous and writes madly.

About the author

Cynthia Marangwanda is a writer and poet from Harare, Zimbabwe, who is passionate about decolonisation and uplifting authentic African spiritual identity. She is a holder of an honours degree in Women's and Gender Studies. Her paternal grandfather, Mr John Marangwanda, is part of the earliest generation of black Zimbabwean writers. The republication of Shards should give this shocking story a new lease of life.

About the reviewer

Memory Chirere is a Zimbabwean writer. He enjoys reading and writing short stories and some of his are published in No more Plastic Balls (1999), A Roof to Repair (2000), Writing Still (2003) and Creatures Graet and Small(2005). He has published short story books; Somewhere in This Country (2006), Tudikidiki (2007) and Toriro and His Goats (2010). Together with Maurice Vambe, he compiled and edited (so far the only full volume critical text on Mungoshi called): Charles Mungoshi: A Critical Reader (2006) His new book is a 2014 collection of poems entitled: Bhuku Risina Basa Nekuti Rakanyorwa Masikati. He is with the University of Zimbabwe (in Harare) where he lectures in literature. Email: memorychirere@yahoo.com