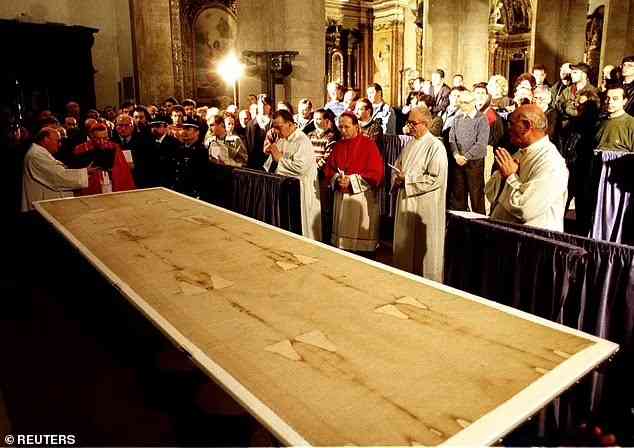

A controversial linen shroud - regarded by some to be the one Jesus was buried in - has baffled the world for more than centuries.

When it was first exhibited in the 1350s, the Shroud of Turin was touted as the actual burial shroud used to wrap the mutilated body of Christ after his crucifixion.

Also known as the Holy Shroud, it bears a faint image of the front and back of a bearded man, which many believers is Jesus' body miraculously imprinted onto the fabric.

But research in the 1980s appeared to debunk the idea it was real after dating it to the Middle Ages, hundreds of years after Christ's death.

Now, Italian researchers who used a new technique involving x-rays to date the material have confirmed it was manufactured around the time of Jesus about 2,000 years ago.

They say the fact the timelines add up lends credence to the idea that the faint, bloodstained pattern of a man with his arms folded in front were left behind by Jesus' dead body.

The Bible states that Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body of Jesus in a linen shroud and placed it inside the tomb.

Matthew 27:59-60 reads: 'Then Joseph took the body and wrapped it in a new linen cloth. He put Jesus’ body in a new tomb that he had dug in a wall of rock. Then he closed the tomb by rolling a very large stone to cover the entrance. After he did this, he went away.'

- Ordinary citizens or foreign capital? July Moyo must choose

- Grace tidings: Relax it is a done deal

- Grace tidings: Relax it is a done deal

- Unpacking Christ; our wisdom (2)

Keep Reading

The burial cloth has captivated the imagination of historians, church chiefs, skeptics and Catholics since it was first presented to the public in the 1350s.

French knight Geoffroi de Charny gave it to the dean of the church in Lirey, France, proclaiming it as the Holy Shroud.

It has been preserved since 1578 in the royal chapel of the cathedral of San Giovanni Battista in Turin, Italy.

The cloth appears to show faint, brownish images on the front and back, depicting a gaunt man with sunken eyes who was about 5ft 7 to 6ft tall.

Markings on the body also correspond with crucifixion wounds of Jesus mentioned in the Bible, including thorn marks on the head, lacerations on the back and bruises on the shoulders.

Historians have suggested that the cross he carried on his shoulders weighed around 300 pounds, which would have left contusions.

The Bible states Jesus was whipped by the Romans, aligning with the lacerations on the back, who also placed crown of thorns on his head before the crucifixion.

In 1988, a team of international researchers analyzed a small piece of the shroud using carbon dating and determined the cloth seemed to have been manufactured sometime between 1260 and 1390 AD.

This technique used the decay of a radioactive isotope of carbon (14C) to measure the time and date objects containing carbon-bearing material.

Some experts have said that the linen's authenticity should no longer be disputed, claiming it was made from flax grown in the Middle East and features a helmet-style crown of thorns on the man's face.

However, others have held on to the notion that it is fake due to the 1988 radiocarbon dating analysis conducted at three different laboratories, which all determined it was only seven centuries old.

For the new study, scientists at Italy's Institute of Crystallography of the National Research Council conducted a recent study using wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS).

The technique measures the natural aging of flax cellulose and converts it to time since manufacture.

The team studied eight small samples of fabric from the Shroud of Turin, putting them under an X-ray to uncover tiny details of the linen's structure and cellulose patterns.

Cellulose is made up of long chains of sugar molecules linked together that break over time, showing how long a garment or cloth has been around.

To date the shroud, the team used specific aging parameters, including temperature and humidity, which cause significant breakdown of cellulose.

Based on the amount of breakdown, the team determined that the shroud of Turin was likely kept at temperatures at about 72.5 degrees Fahrenheit and a relative humidity of around 55 percent for about 13 centuries before it arrived in Europe.

If it had been kept in different conditions, the aging would be different.

Researchers then compared the cellulose breakdown in the shroud to other linens found in Israel that date back to the first century.

'The data profiles were fully compatible with analogous measurements obtained on a linen sample whose dating, according to historical records, is 55-74 AD, found at Masada, Israel [Herod's famous fortress built on a limestone bedrock overlooking the Dead Sea],' reads the study published in the journal Heritage.

The team also compared the shroud with samples from linens manufactured between 1260 and 1390 AD, finding none were a match.

'To make the present result compatible with that of the 1988 radiocarbon test, the Shroud of Turn should have been conserved during its hypothetical seven centuries of life at a secular room temperature very close to the maximum values registered on the earth,' the study reads.

Lead author Dr Liberato De Caro said in a statement that the 1988 test should be deemed as incorrect because 'Fabric samples are usually subject to all kinds of contamination, which cannot be completely removed from the dated specimen.'

'If the cleaning procedure of the sample is not thoroughly performed, carbon-14 dating is not reliable,' he added.

'This may have been the case in 1988, as confirmed by experimental evidence showing that when moving from the periphery towards the center of the sheet, along the longest side, there is a significant increase in carbon-14.'

Scientists have long been studying the Shroud of Turin with hopes of solving the centuries-old mystery.

More than 170 peer-reviewed academic papers have been published about the mysterious linen since the 1980s, with many concluded it to be genuine.

Testing in the 1970s looked at whether the images were made through painting, scorching or other agents, but they none could be confirmed.

Another group of experts from the Institute of Crystallography announced in 2017 that they had found evidence that the shroud featured the blood of a torture victim.

They claimed to have identified substances like creatinine and ferritin that are usually found in patients who suffer forceful traumas.

The alleged findings contradicted claims the face of Jesus was painted on by forgers in medieval times.