LAST week’s article on the law governing criminal liability of directors and corporate persons, anchored on the recently concluded case involving Mike Chimombe and Moses Mpofu, elicited robust engagement from readers.

The responses raise issues that merit deeper interrogation, not least because they go to the heart of corporate personality, criminal accountability and the proper role of the courts in an adversarial system.

One of the central questions posed by readers concerns whether Blackdeck Private Limited was a duly registered company at the time the tender documents for the US$87 million Presidential Goat Pass-On Scheme were submitted.

This issue is not merely technical; it is fundamental. The legal status of the entity directly informs the arguments around corporate and personal liability.

Closely related is the question of piercing the corporate veil. The law recognises a company as a separate legal person, distinct from its directors, shareholders and employees.

Ordinarily, this separation shields individuals from personal liability for corporate acts. However, courts may pierce the corporate veil in exceptional circumstances, particularly where the corporate form is abused to perpetrate fraud or injustice.

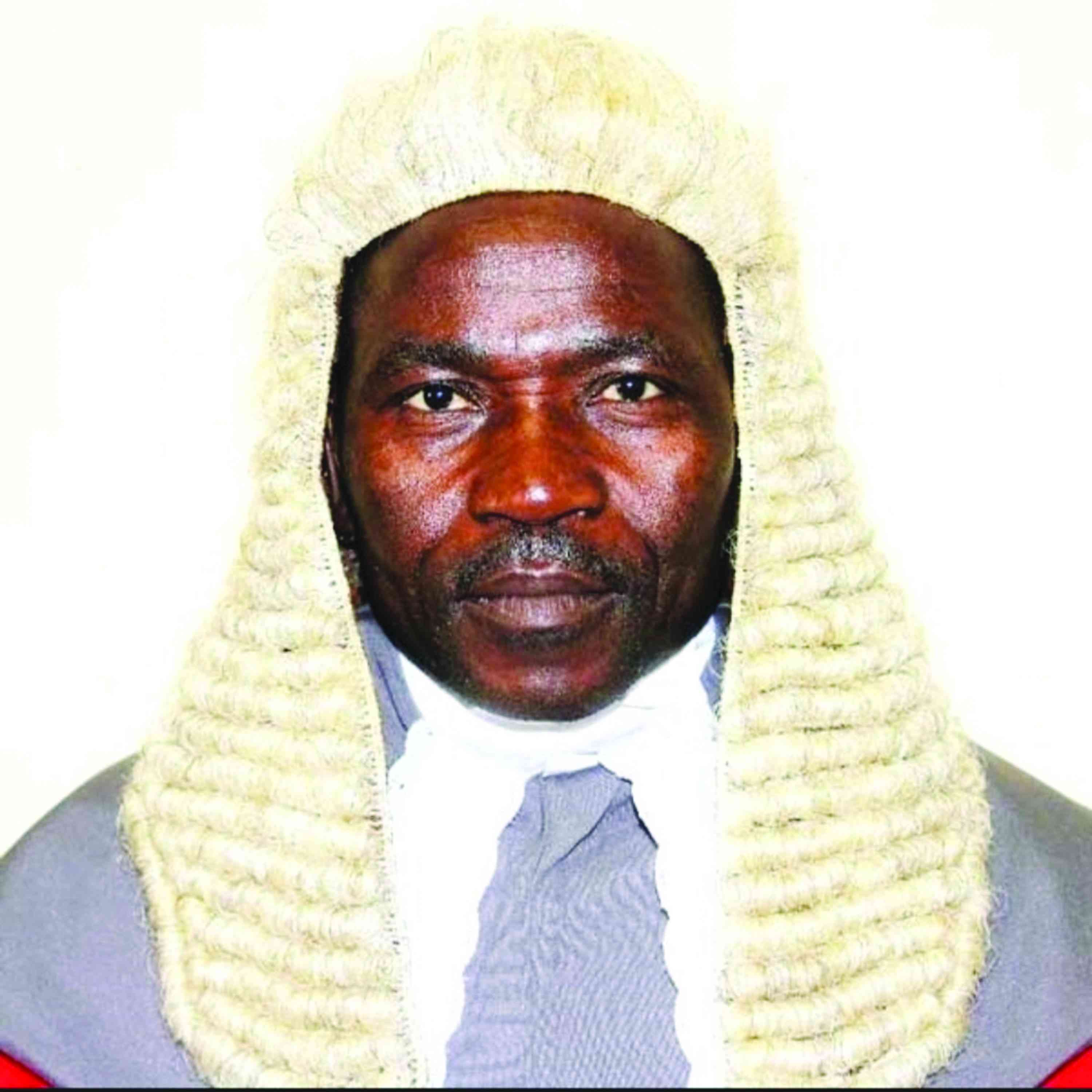

In judgment HH 780-25, Justice Pisirayi Kwenda was unequivocal on one point: Blackdeck Private Limited was, indeed, a registered company, with three directors, Moses Mpofu, Hazvinei Kabisira and Tinashe Chimombe.

Notably, however, only Mpofu stood trial. Yet, without appearing before the court, the other two directors were ordered to restitute part of the approximately US$7 million lost by the State as a result of the fraud. That aspect alone warrants separate and careful scrutiny.

- Zanu PF socialite granted $50 000 bail

- Rick Ross show marred by confusion

- Popular nightclub manager granted $100k bail for rape

- Judge slams police over arrest

Keep Reading

In his reasoned judgment, Justice Kwenda concluded that although Blackdeck Private Limited existed as a registered entity, the actions of Mpofu and Chimombe were not authorised by the company and were not undertaken in its interests. On that basis, the company itself could not be held criminally liable.

The learned judge stated: “The argument that it was obvious that Blackdeck Livestock and Poultry Farming referred to Blackdeck (Pvt) Ltd because Blackdeck (Pvt) Ltd is the owner of the certificate of incorporation, CR14 and CR6 submitted with the bid, is fallacious.

“This is just a case of stolen identity as argued by the State, although not in so many words. Legal documents belonging to Blackdeck (Pvt) Ltd were fraudulently used by the perpetrators of this crime to give Blackdeck Livestock and Poultry Farming a veneer of legal personality.”

Put simply, the court found that Mpofu and Chimombe acted outside the interests of Blackdeck Private Limited by “stealing” its corporate identity.

Consequently, they were not entitled to the protections ordinarily afforded by section 277 of the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act.

That section shields directors, shareholders and employees only where their conduct is sanctioned by the company, typically through board resolutions or contracts of employment.

Section 277(2) provides that: “Any conduct on the part of a director or employee of the corporate body, or any person acting on instructions or with permission, expressed or implied, given by a director or employee of the corporate body, in the exercise of his or her power or in the performance of his or her duties as such a director, employee, or authorised person, or in furthering or endeavouring to further the interests of the corporate body, will be deemed to have been the conduct of the corporate body.”

Ordinarily, for a court to conclude that a company did not authorise particular conduct, one would expect the company to be a complainant or, at the very least, a witness supporting the State’s case.

That, however, was not the position in this matter. Ordinarily, for a court to conclude that a company did not authorise particular conduct, one would expect the company to be a complainant or, at the very least, a witness supporting the State’s case. That, however, was not the position in this matter.

It is against this backdrop that Chimombe and Mpofu have since approached the appellate courts, arguing that the trial court “went on a frolic of its own” by making findings on issues that were not squarely before it.

They contend that this approach infringed their constitutional rights. Section 70(1)(a) of the Constitution guarantees every accused person the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty, while section 18(1) of the Code requires the State to prove every essential element of an offence beyond a reasonable doubt. Where doubt remains, the proper verdict is an acquittal.

Zimbabwe operates an adversarial criminal justice system. The State bears the burden of proving its allegations beyond reasonable doubt, not on a balance of probabilities. Where that standard is not met, a conviction risks amounting to a misdirection.

Turning to the second issue, the piercing of the corporate veil, it is my considered view that once the court concluded that Mpofu and Chimombe were not acting in the interests of Blackdeck Private Limited, but had instead appropriated its identity for fraudulent purposes, the veil-piercing inquiry became largely academic.

Section 277 only protects those acting within the authority of the company. Where corporate identity theft is established, the defence of separate legal personality falls away.

Justice Kwenda nevertheless addressed the issue directly, observing: “A company does not exist in human form. It is trite that in common law a company is a fiction which exists only in the eyes of the law, and is described as a legal entity formed by a group of people to conduct business, with the key characteristic that it is separate from its owners and can own assets, incur debt, and sue or be sued.”

He said this separation creates limited liability for the owners (shareholders), protecting their personal assets from company debts.

“Companies have owners (shareholders) and directors who control operations. There can never be a case of a fiction, which is not a legal entity supplying goats,” Justice Kwenda stated.

“The criminal design was that the perpetrators would hide behind the facade of the corporate veil they had created to escape criminal liability for their actions.

“The protection offered by the corporate veil was another calculated reason behind clothing Blackdeck Livestock and Poultry Farming with the stolen corporate identity of Blackdeck (Pvt) Ltd.

“In the event that the crime is discovered, the perpetrators would hide behind the corporate veil,” the judge ruled.

On the facts accepted by the court, all government payments were made directly into Blackdeck Private Limited’s bank accounts.

The company also secured bank guarantees in its own name totalling US$23 million, which were lodged with the Ministry of Agriculture.

This gives rise to troubling and unresolved questions. If Blackdeck Private Limited’s identity was indeed stolen, how did it come to process securities for a tender to which it was allegedly not a party?

Why did it receive payments from that tender, and how did it proceed to utilise those funds to partially fulfil contractual obligations? These contradictions sit uneasily with the notion of a wholly innocent corporate victim.

Ultimately, the Chimombe and Mpofu matter exposes deep and unresolved tensions in Zimbabwean corporate criminal law.

It underscores the limits of the corporate veil and affirms that directors cannot hide behind corporate personality where their conduct is fraudulent and unauthorised.

As the appeal unfolds, it will be critical to see how the courts reconcile the protection of corporate integrity with the imperatives of personal accountability and constitutional fairness.

Mhlanga is a law student at the University of Zimbabwe.