FOR over 20 years, villagers from Lower Gwelo Ntabamhlophe Drink village have relied on one ramshackle bus that trundles on rugged roads, a grim testament to the severe transport crisis afflicting remote rural areas across Zimbabwe.

In these neglected communities, people often walk long distances just to find firewood or water, and accessing urgent medical services at dilapidated hospitals and clinics is an ordeal.

The journey to Gweru Provincial Hospital, around 71km from the central business district (CBD), is particularly gruelling.

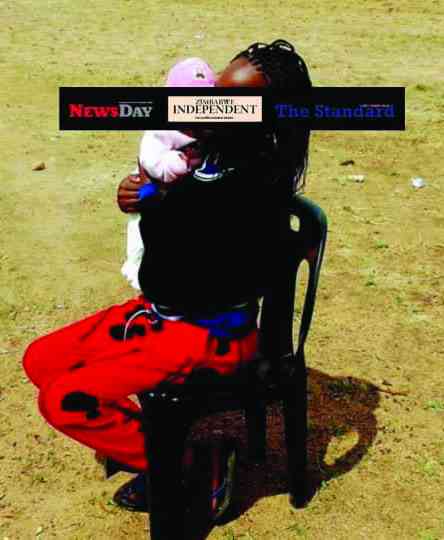

For Siphiwe Tshabalala, a young mother, the memory of her labour journey is one she cannot forget.

Tears fill her eyes as she recounts the experience that nearly turned deadly.

Her mind raced with panic as she realised the nearest medical facility was far beyond reach. It was a matter of life and death.

Desperation forced her to make a tough choice: she decided to travel by scotch cart to Maboleni, a perilous 15km journey from her home. But as she travelled, her worst fear came true — her water broke.

“Amniotic fluid came out at Ascot High School on my way to Gweru Provincial Hospital, about 7km away from the CBD,” Tshabalala recalled.

- Stanbic voted best African bank

- Business opinion: Building brand loyalty

- Business opinion: Building brand loyalty

- Environmentalist hails BCC new parking system

Keep Reading

A trusted health information website Medline Plus describes amniotic fluid as layers of tissue that hold the fluid surrounding a baby in the womb.

In most cases, these membranes rupture during labour or within 24 hours before starting labour.

Ntabamhlophe’s only transport to Gweru is a single, unreliable bus operated by T-One Tours, which departs at the unsafe hour of 4am.

Villagers often describe it as their only option — a bus prone to breakdowns and delays.

For Tshabalala, waiting for another day was impossible, leaving her with the scotch cart as her only means of transport.

“I was expecting my child on 26 September (plus or minus two weeks) according to the last visit at Ntabamhlophe clinic. Then on 8 September around 6am I started feeling slight labour pains," she narrated.

“Unfortunately, our only bus had left around 4am. My brother spoke to our neighbours who took us on a scotch cart to Maboleni shopping centre about 20km away where we could get transport to Gweru.

“On the way, I could feel all the bumps on the dust road and at the same time we wanted to move with time as the pain was gradually increasing. Luckily, we got transport and we paid to take the back seat in a Honda Fit which took us to the hospital which is about 40km away.”

Tshabalala arrived at Gweru Provincial Hospital around 3pm and the midwives assessed her only to find out she was 7cm with 2cm away from delivery.

After about three hours, she was blessed with a bouncing baby girl, whom they named Nkosiphile (God has given).

Her initial plan was to go to her friend’s residence in Gweru seven days before September 26 — the due date — since she has no relatives in Zimbabwe’s fourth largest city.

“At Ntabamhlophe clinic, they do not take the first-time expecting mothers unless it’s the second time going up. So, I was supposed to be closer to Gweru Provincial Hospital for delivery,” Tshabalala explained.

“So, my plan was to be some days before the due dates so that I won’t bother my friend, but it did not go as I planned. I was so happy for the normal delivery; I am a happy mother now.”

According to Mlibazisi Bhebhe, a lifelong resident of Ntabamhlophe, the transport crisis has only worsened over the years, exacerbated by the deteriorating road network and failing infrastructure.

He recalls that before the land reform of the 2000s, there were four buses serving the area, with two Tawuya Coach and two Zupco buses offering routes to Bulawayo, Harare, and Gweru.

Now, he laments, villagers are left to rely on just one bus.

Bhebhe said they pay US$4 for bus fare during normal days and US$6 during public holidays, like Christmas.

“My late grandparents say before the landgrabs experience in the 2000s, there were four buses,” he said.

“The two coaches were leaving Ntabamhlophe at 3am for Bulawayo and Harare routes. The other two buses were going to Gweru, one would go via Dimbamiwa, Bhembe, Siparo to Maboleni, while the other one used Shagari St Faith Road.

“I am 30 years old now and we have been relying on a single bus since I was born. You can barely see a kombi or a Honda Fit. I remember the AVM bus during my primary school days. We used to sing with joy when we saw the bus arriving from town. Transport problems have been like this for years.”

One Honda Fit driver, Mthokozisi Sibanda, explains why operators rarely travel to Ntabamhlophe, describing the hazardous road conditions that turn a trip from Gweru to Ntabamhlophe into a four-hour journey, particularly during the rainy season.

“It takes about two hours to drive from Gweru to Maboleni if you do not love your car. Then from Ngadele turn-off to Ntabamhlophe is a dust road, so I need four hours from Gweru to Ntabamhlophe. It’s not easy, especially during the rainy season. This makes it difficult for Mshikashika drivers to go to Ntabamhlophe because we will only make two trips,” he explained.

Newly-elected Vungu legislator Brown Ndlovu (Zanu PF) recognises the need for a multi-stakeholder approach to address the crisis, while Vungu Rural District chief executive officer Alex Magura notes that improving roads and transport is a top concern raised in their recent budget consultations.

Knowledge Kaitano, chairperson of the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Transport and Infrastructure, has also said there was need to prioritise remote areas like Ntabamhlophe.

According to the World Health Organisation, about 287 000 women globally died during or after childbirth in 2020, with 95% of these deaths occurring in low and lower-middle-income countries.

Many of these tragedies were preventable, highlighting the consequences of inadequate healthcare access in impoverished regions.

Tshabalala's story is a stark reminder of the challenges faced by rural communities in Zimbabwe.

The lack of reliable and affordable transportation, coupled with poor infrastructure and lack of health facilities, have devastating consequences, particularly for pregnant women and those in need of urgent medical care.