A walk through the cities of Zimbabwe, a nation renowned for its resilient spirit and peace-loving nature, reveals a grotesque political atmosphere where intensified state crackdown on dissenters is unfolding.

In street corners, commuter bus ranks, and vegetable marketplaces, whispers of state brutality grow louder day by day.

Fuming, citizens discuss reports of the brutal arrest and detention of 78 opposition members on June 16, 2024, along with the latest July 31, 2024, arrest and torture of four human rights defenders: Robson Chere, Namatai Kwekweza, Samuel Gwenzi, and Vusumuzi Sibanda.

This crackdown on opposition and human rights defenders during the Sadc industrialisation week has been glaring and brazenly daring in the state’s disregard for constitutional rights and democratic norms.

It has also shaken the key African values of hunhu/ubuntu — the very foundations upon which the republic is glued together.

In African hunhu/ubuntu culture, it is taboo for a man of the house to chastise a child or quarrel with his wife in front of visitors.

No matter the cause, disputes are resolved peacefully and amicably to show hospitality and reverence not only to the important guest but also to preserve the family name from consequential bad publicity.

This is a common moral position (CMP), establishing the foundation of African society. Hunhu/ubuntu are basic norms “… that flow within African notions of existence and epistemology in which the two constitute a wholeness and oneness.”

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Bulls to charge into Zimbabwe gold stocks

- Ndiraya concerned as goals dry up

- Letters: How solar power is transforming African farms

Keep Reading

However, the government’s glaring defiance of the two foundations of society — constitutional norms and culture — has cast a dark shadow over the country’s public posture, its culture, and its democratic aspirations.

The Zimbabwe Democracy Institute’s argument is that the crackdown is a political legitimacy deficiency syndrome, the symptoms of later stages of a decaying social contract upon which the very existence of government, and consequently the state, lies.

In this Zim-agora, we diagnose the underlying problem symptomised by this crackdown, exploring its implications on the social contract, the legitimacy of the state, and the future of Zimbabwe.

Through a blend of critical analysis and tapping into African knowledge systems, we delve into how a traditionally peace-loving and risk-averse populace is being pushed against the wall in undemocratic ways.

The metaphor of teaching a tortoise to hurry aptly captures the absurdity and urgency of the situation, as the state’s heavy-handed tactics inadvertently fuel the very unrest they seek to suppress.

The recent onslaught against the opposition and civil society activists is best understood within the context of a securocratic state — a state that prioritises regime security over citizens’ rights and demands, using coercive state apparatus to forcefully coerce its political rivals into submission or elimination.

It is within this state context that the crackdowns are deployed for regime survival.

Three key strategies are observably deployed to achieve this end. First is the criminalisation of dissent.

In recent years, the Zimbabwean government has systematically targeted opposition leaders, journalists, and activists using the coercive state apparatus to protect the ruling elite’s survival.

For instance, journalist Hopewell Chin’ono was arrested in July 2020 after exposing a multimillion-dollar Covid-19- related corruption case. Political activist Jacob Ngarivhume was arrested in July 2020 for calling for a nationwide protest against government corruption, and opposition leader Job Sikhala spent months in prison for his political views

Second is use of coercive state apparatus for the suppression of protests.

The state has frequently used excessive force to disperse protests.

Examples include the violent crackdown on August 1, 2018, protests against the delayed release of election results, which resulted in civilians being shot by the army in the capital, Harare.

The January 2019 protests against rising living costs saw the army and police deployed across the country, resulting in many deaths and brutal injuries. Health workers protesting poor working conditions were also criminalised, with some, like Peter Magombeyi, being abducted and tortured.

Third is the use of lawfare, solidified through the enactment of the “Patriotic Bill,” which further criminalizes dissent.

As argued earlier, a ruling elite that survives through these tactics suffers from a political legitimacy deficiency syndrome — the symptoms of later stages of a decaying social contract upon which the very existence of government, and consequently the state, lies.

The social contract between the state and its citizens in Zimbabwe has entered later stages of decay. The government’s reliance on security forces to maintain order highlights a lack of trust and legitimacy — the two values needed to run a democratic republic.

The political legitimacy refers to a voluntary support given by citizens to the political system by virtue of being perceived to be the rightful authority.

Where the ruling elite relies on force and coercion to enforce policy, it is a sign that they have lost their legitimacy.

The legitimacy of the securocratic state and the ruling elite has been eroded by various factors, such as the decline in electoral support, the deterioration of the rule of law, the violation of human rights, the closure of the civic and democratic space, the disputed elections, the endemic corruption, the poor service delivery, the economic collapse, and the social unrest.

The erosion of the social contract has been evident in successive disputed elections, reports of biased electoral management bodies populated with loyalists of the ruling Zanu PF elites, deployment of quasi-securocratic entities like the Forever Associates Zimbabwe (FAZ) to interfere with the electoral processes, and the deployment of the police to block opposition campaigns detailed in the Sadc and EU election observer missions’ reports, among others.

These are telltale signs of a ruling class that knows it cannot win a free contest for power, as it has lost the trust of the citizens.

The deployment of the army and the crackdown on dissent are indicative of a government more concerned with preserving its power than addressing the needs and aspirations of its people.

Thus, the recent deployment of security forces to quell possible protests is a clear indication of the government’s intent to maintain control and suppress any form of dissent, as it is likely to lead to citizens’ transition agency.

This move reflects deep-seated fears within the ruling elite about potential uprisings and public protests.

The heavy-handed approach is reminiscent of the tactics employed during Robert Mugabe’s final days in power, where government reshuffles and crackdowns were used to quell opposition and maintain a grip on power.

The current attacks on civil liberties are not merely responses to external threats but also reflect internal fissures within the ruling party.

Infighting and power struggles have created an atmosphere of paranoia, leading to preemptive measures to prevent any faction from hijacking public protests.

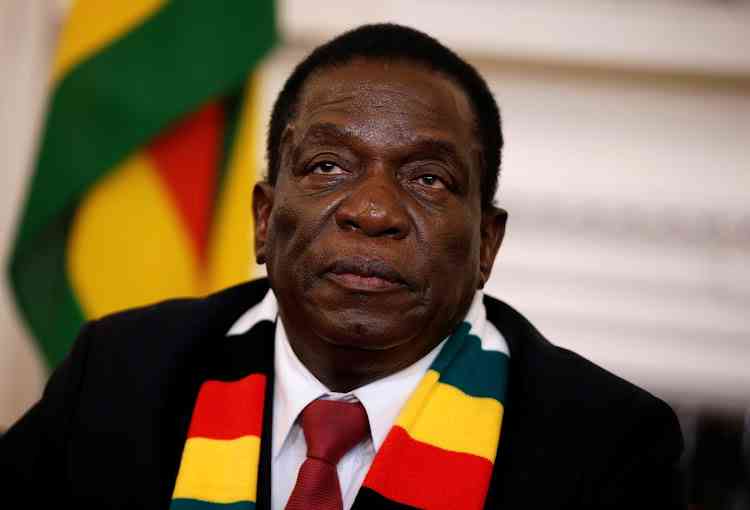

These internal fissures within the ruling Zanu PF party are evident in their nationwide political activities promoting President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s continued stay in power until 2030, despite constitutional provisions (i.e., sections 91 and 328 (7)) that prohibit him from remaining in power for more than two terms ending in 2028.

This is encapsulated in a slogan popularized by Mnangagwa’s allies in Masvingo and Midlands provinces: “2030, VaMnangagwa vanenge vachipo vachitonga,” meaning “in 2030, Mnangagwa will still be there, ruling.”

Discrediting the campaign, then Zanu PF commissar Mike Bimha stated in April 2024 that the new slogan calling for the extension of PMnangagwa’s tenure beyond 2028 is not recognised by the party.

Lessons from the last days of Mugabe’s rule are worth reiterating.

In November 2017, a similar critical juncture occurred when the faction aligned with current Mnangagwa teamed up with the military, civil society, and the opposition to capture state power from the late Mugabe.

African history is rich with case studies showing that once a power transition through a coup d’état occurs successfully, successive transitions are likely to follow suit, as military takeover becomes revered as the most effective means to state power.

This is especially true where democratic platforms for expressing dissent and alternating power are rendered defunct by the authoritarian regime.