TIGER Woods was interviewed on television at the age of 2, played his first tournament aged 5 and was the first person to win three straight Amateur US Open Championships. Serena Williams made her pro debut at the age of 13. Michael Phelps achieved his first world record in swimming at the age of 16. Talent may be latent for some (as we have considered in a previous article) but in people like those mentioned above it is patent – very patent.

The real question then is: what do they do with it? It is fair to say that those mentioned above have done alright with their talent – Tiger Woods has won 15 Majors and more tournaments than anyone else; Serena Williams has won 23 Grand Slam titles; Michael Phelps won 23 gold medals, three silver and two bronze over five Olympic Games. However, it has not always been the case that such patent talent brings rewards and results.

Let us consider this story. A man who loved his sport had three children and sent them to a school that offered plenty of sporting opportunities so that they could develop their talents in that arena. The oldest son was a supremely gifted child from a very young age who loved hockey, cricket, tennis, golf and athletics; he threw himself into all these sports and gained recognition at school, provincial and national age group levels.

The second child was a diligent and determined girl who gave her all within the extent of her abilities and was pleased to represent her school and provincial teams in netball and volleyball. The third child proved to be talented at soccer but he did not like the coach who he thought was too critical and unfairly demanding of the players, so he preferred to hide in the background and not be selected for any of the school soccer teams.

There came a time for each of these children when their father considered their futures. The eldest child who had exceeded all expectation in all five sports was rewarded by universities who were falling over each other to offer him a sporting scholarship. He went on to represent his country in those sports.

The middle child had done well with her sports to continue to play for a local club at a professional level and flourished at that level through hard work. The last born, however, sadly discovered that universities were keen only to recruit youngsters who had a sporting dimension and his father would not pay for his further development.

There was another successful sportsman who had two sons and who longed that they would enjoy sport as much as he did, playing with him whenever possible. The youngest son showed immense talent and set about making the most of his sporting ability.

He applied for a scholarship for a top university overseas where he played sport all the time, opening up doors all along the way and gaining great recognition and success. Fame and fortune followed him but slowly those proved to be major distractions to him and he trained less and less in practices, tried less and less in matches and soon found himself not even being selected for any of the teams. He naturally was worried about what his father (who had always been his biggest supporter and indeed inspirer) might think of him; after all, this young lad had had it all at a young age but blew his chance.

This man’s older son also had great potential and talent which he used within his local sphere. He did not go overseas to play his sport but day in, day out, trained and played quietly, consistently, conscientiously at all times. He had much patent talent, which pleased his father greatly, even if he did not get the headlines, for the right or wrong reasons, like his brother. He looked down on his brother for wasting his talents, complained about such a waste even, but he still did what he could.

We may well recognise certain parallels to parables told many years ago yet see parallels in sporting arenas today, where we come across prodigies, those with excellent abilities, whose talent is not latent but patent; it shines out from them.

The question is: how do they use them? There are many wonderful examples of sporting prodigies who, like Tiger Woods, Serena Williams, Michael Phelps all started young, achieved great success, making the most of their patently prodigious talent.

There are others who have done what they can with what talent they have but then there are, too, those who have wasted their great talent by hiding it, dropping it, ignoring it, despising it, for all sorts of different reasons, including us as coaches. However, the bottom line is this: we must ensure that our prodigies do not become prodigals. He who has ears to hear, let him hear!

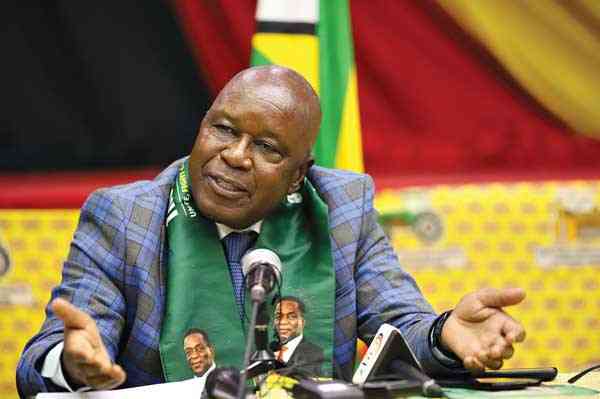

Tim Middleton is a former international hockey player and headmaster, currently serving as the Executive Director of the Association of Trust Schools Email: ceo@atschisz.co.zw