SOME of the country’s leading business leaders capitulated this week, telling the Zimbabwe Independent that grappling with heavier power tariffs was better than having rolling blackouts, which result in more corporate graveyards.

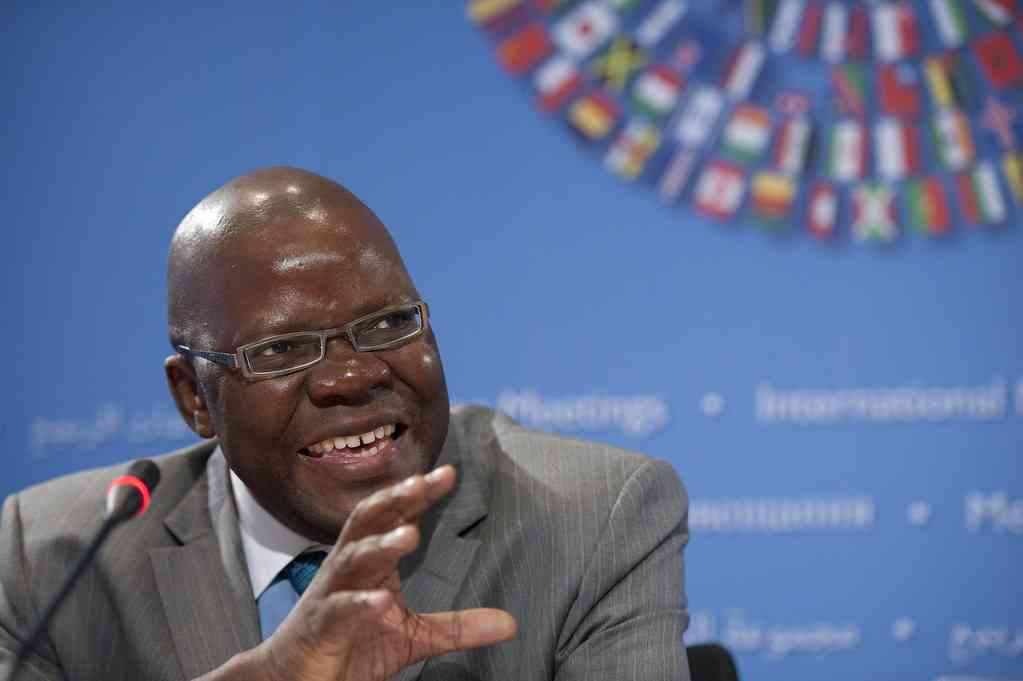

In any case, there were more corporate failures out of blackouts, according to Christopher Mugaga, chief executive officer at the Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce (ZNCC), than those suffocating under power tariffs.

Asked if business was relaxed because it passes costs to consumers in the event of a fresh tariff hike, Mugaga said if industries ran at healthy levels, they were likely to call off any price rage, and consumers would be safe. His remarks, shared by other industrialists and economists, followed weeks of debate over debt-ridden power utility, Zesa Holdings’ planned tariffs increases that it says will give it capacity to import electricity and service a hefty debt.

Zimbabwe has already suffered under drastic power cuts, which the ZNCC projected in February may wipe up to US$4 billion out of industries this year, in the absence of bold action.

“The tariff is a small issue,” Mugaga told the Independent, as the Chamber of Mines of Zimbabwe warned of serious problems if Zesa’s proposed US$0,02 per kilowatt hour (kwh) power hike is approved.

“The challenge comes when we don’t have power, and we still have to pay. That is something else. Businesses are not collapsing because of the tariff. They are collapsing because of power unavailability,” Mugaga said.

Keep Reading

- Low tariffs weigh down ZETDC

- ‘Systems disturbance hits Hwange Power Station’

- Power crisis hits Proplastics factory

- Zesa doubles power charges

“If they increase the power tariff and electricity is guaranteed, the impact won’t be much. Those affected by a tariff increase already owe Zesa. Most of them are politically exposed institutions.”

The Independent understands that out of about ZW$150 billion (US$26,6 million at the interbank rate of US$1:ZW$5 639) owed to Zesa, the bulk of the debt is held by state agencies, firms and local authorities.

Zesa’s planned hike will see consumers paying about US$0,12 per kilowatts hour (kwh), which is much lower than tariffs of up to US$0,20/kwh being paid in some of Zimbabwe’s southern African countries.

But a tariff review, as planned by Zesa, will be felt more in the mining industry, which may see companies in the sector paying about US$0,14/kwh.

In a way, Zimbabwe is paying the prize of authorities’ procrastination to tackle a power crisis that they knew back in 2003 would tear through southern Africa by 2007.

Economies that were exporting power to Zimbabwe were growing at double digit rates at the time. There were already signs that from 2007, these would be overwhelmed by steeper demand in their own economies, according to Tapiwa Sibanda, head of strategy at Trade Winds.

He said government was aware this would force these countries to cut back on exports to Harare, a perennial defaulter.

These economies were Namibia, Zambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique and South Africa, which are now struggling to power its own industries.

In the face of impending threats, Zimbabwe only acted after already falling into power problems in 2013, when government began the refurbishment of the 750MW Kariba South Hydroelectric Power Station, spending US$553 million.

On completion in 2018, power output increased to 1 050MW at Kariba.

“But prolonged droughts in the Zambezi River basin have triggered serious generation cutbacks at Zimbabwe’s biggest power facility,” according to Sibanda.

There have been queries over how resources were expended there instead of prioritising Hwange, which is less likely to be affected by droughts.

Today, generation has improved at Hwange after government spent US$1,5 billion to rebuild Units 7&8, but not enough to fire up industries that have been demanding more as new mines and furnaces come on stream. The country requires up to 2 000MW, but is producing much less than this, leading to Zesa’s plan to hike the tariff to provide funding for imports, along with servicing the US$1,5 billion Chinese loan.

Respect Gwenzi, an economist at advisory firm, Equity Exis, said it was normal for companies, including Zesa, to set prices that reflect their costs of production. But he said the quality of products, and consistency of supply in the case of Zesa, was vital, especially considering it still enjoys significant monopoly.

“Pricing is a function of your costing and also the nature of market competitiveness,” Gwenzi told the Independent.

“You can be a monopoly just like Zesa, but your tariff has to be competitive enough to match the regional standards.

“At the end of the day, the major question is, is Zimbabwe not better off importing at a lower rate than if you are increasing the cost,” he pointed out.

But during the run up to the August 23 elections, President Emmerson Mnangagwa declared the end of the debilitating crisis after commissioning Units 7&8, which added about 600MW to the national grid.

Last week, Denford Mutashu, president of the Confederation of Zimbabwe Retailers, told the Independent that industries wanted consistency in power supply — they were less worried about the tariff.

“Inconsistent electricity supply is a cost to doing business,” Mutashu said.

“Charging sub-optimal tariffs is a burden to power supply authorities. If a review of tariffs assures the nation of constant power supply, it is a better option for business than facing the cost of alternatives like generators,” he added.

The Chamber of Mines Zmbabwe raised the red flag last week, warning that with commodity prices in a tailspin, the timing for a power tariff increase was wrong for the US$12 billion sector. The mining industry is battling to forestall a fresh wave of bankruptcies provoked by steep increases in statutory obligations and hefty power tariffs, which have rocketed by 40% in the past eleven months.