CLIMATE action is regarded as the core issue of our time in scope, content and value. To mitigate and adapt to the negative impacts of climate change, climate action is key, transformative and instrumental from a wide and broad network of a variety of actors. Although climate change is highly driven by science, climate action is inclusive, cross-cutting and multidisciplinary.

As such, the solutions to the climate change impacts will not come from scientists only but everyone and every sector, hence it needs collective and collaborative efforts.

Climate action is deeply rooted and premised on sustainable development goal (SDG13) and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Paris Agreement take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. From the general point of view, climate action constitutes, a range of activities, mechanisms, policy instruments, with the aim to reduce the severity of human-induced climate change and its impacts. In this regard, climate action is not treated in isolation but there is need to connect it with other sustainable development goals (SDGs).

Therefore, without climate action, negative impacts of climate change will undermine 16 other SDGs. The integrative and collaborative nature of SDGs will enable climate action to reinforce all the 17 SDGs.

A wider perspective of the climate change narrative is unfolding everywhere, but it is being undermined by the global scale climate inadequacies, voluntary, avoidable or unavoidable. Furthermore, since decisions and outcomes reached at international climate change fora are politically driven and not environmental, political will is central to decisionmaking.

Therefore, it is the political will or lack of it which drives the conference of parties (COPs) conventions, funding allocations and disbursement, including the carbon emission thresholds.

The bulk of climate action strategies are locally initiated and driven but there are supposed to be institutional enablers designed to make climate action happen.

Every country has these institutional enablers that require maximum climate support and backing from the government. Local climate action interventions are spearheaded from within, that is domestic or in-country initiatives designed to culminate into concrete climate action solutions.

- COP26 a washout? Don’t lose hope – here’s why

- Under fire Mnangagwa resorts to Mugabe tactics

- Out & about: Bright sheds light on Vic Falls Carnival

- How will energy crunch transition impact transition to renewables?

Keep Reading

These are tangible and observable programmes designed to improve food security, livelihoods recovery, small-scale water reservoirs, smart agriculture, afforestation, climate education and awareness raising, among others, all adaptive in nature. Then there are those designed to promote mitigation co-benefits like reduction of greenhouse gases, renewable energy transition and low carbon emissions in the agricultural sector, transport, manufacturing, forestry, tourism and mining sectors.

The above stated co-benefits are under threat from lack of political will on the part of governments, to get things done in positive and transformative ways. It is the government of the day which spearheads and chaperones climate action programmes for them to have a national outlook.

These are the climate milestones, co-benefits and the right thing to do too. When government supported and driven climate action programmes like Pfumvunza/Intwasa/Conservation farming bear fruits, the government goes over the moon celebrating. In contrast, when the government fails to regulate and manage land-use practices, when small-scale mining land degradation threatens road infrastructure, it is the duty of the same government to show political will to stop such anti-climate behaviours. The most unbecoming behaviour is for government to fail to walk the talk when some environmentally destructive behaviours appear to be ignored yet the damage is immeasurable.

On the international level, climate action interventions have been paralysed by lack of commitment, self-centredness, double-talk, international policy inconsistencies, political grandstanding, climate inaction and big-brother approaches. This is where the main polluting actors fit in, oozing with the power of stinking riches and arrogance, where their needs rule and override everything environmental and foregrounding their political interests.

There is will and determination on local climate action strategies, with local actors geared to deal with negative impacts of climate change but lacking support from governments. Many developing nations poorly fund climate action interventions even when strong policies are there on paper. As a result, local communities are exposed by lack of cushioning from governments.

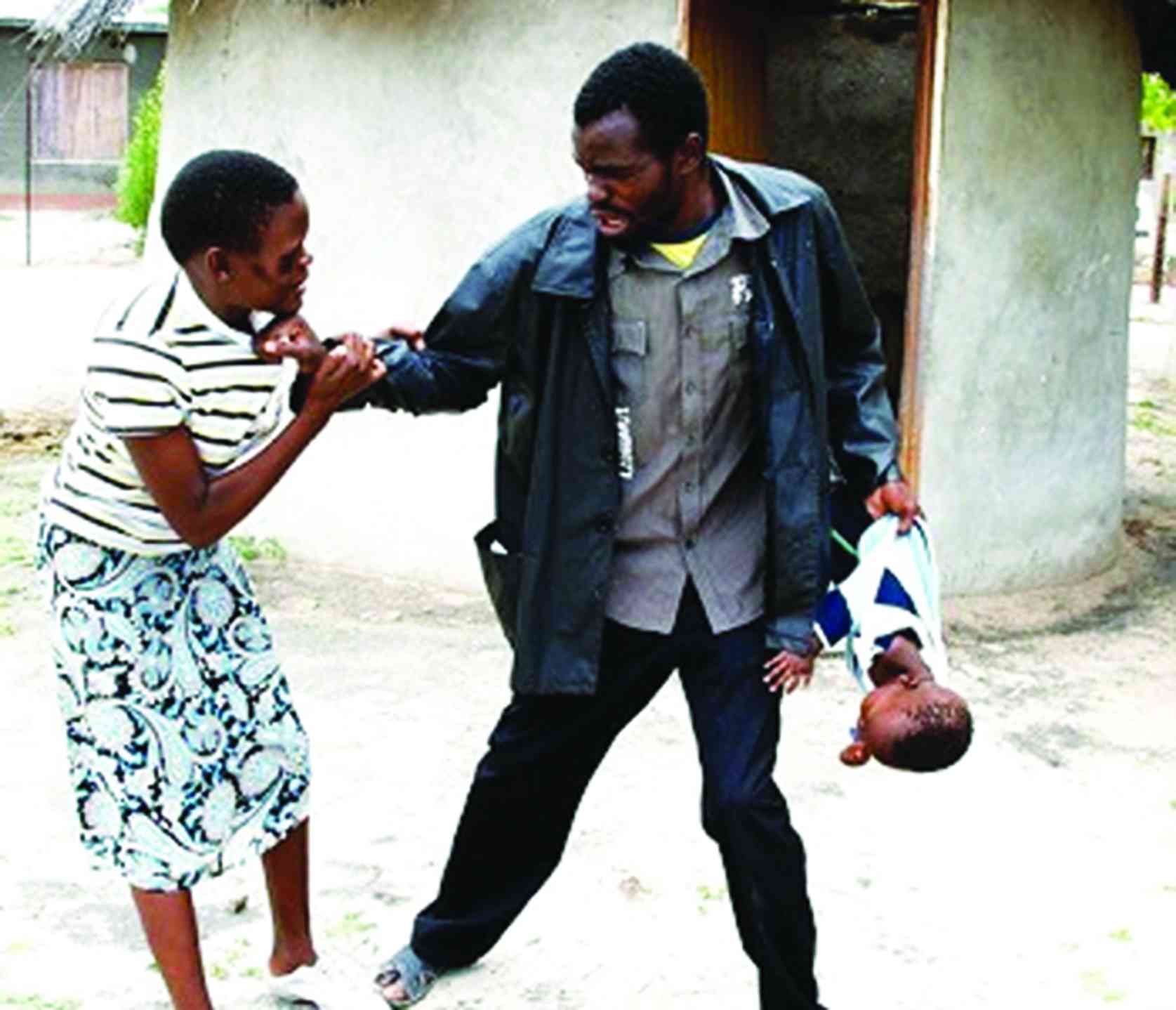

These governments have the audacity to commit land-use crimes while on the other hand, they are preaching ecological governance and environmental stewardship. In short, decision and policymakers are making wrong decisions against the climate action will of local communities.

Besides the funding they get from international donors and multilateral financiers, few local players and financiers through their corporate social responsibility, public-private partnerships, many governments in developing countries are not committed to funding locally-driven climate action strategies.

Some cases in point are that developing countries are failing to fund basic energy transitions and to deliver their local communities from perpetual energy poverty, environmental health and well-being. This also includes failure to deal with climate-driven mental health issues which are currently taking centre stage.

In many developing countries, interdisciplinary climate action involvements are weak simply because climate scientists and other scientific technical experts, still think that climate change is their commodity and community of practice, ringfenced and gatekept. This is done to keep away other experts and sectors from the climate action cake. In this regard, social climate scientists, communicators, educators, the arts, writers, the media, sportspersons, religious people, traditionalists, among others, face marginalisation from the real experts with lots of climate science in the head. It is this type of climate action gatekeeping that stalls climate action growth and interventions. In the developed countries, it is the municipalities and local governments that spearhead climate action programmes such as Net-Zero while in developing countries NGOs fund climate action programmes with government ready to claim credit for political expediency. It is always a struggle to have sustainable links between the country’s national climate policies and envisaged climate action outcomes.

This culminates in increased gaps between climate action interventions on the global scale and the local scale initiatives.

In developing countries, climate action is not a matter of choice if it does not bring quick financial gains at the expense of the long term and sustainable ones. That is why developing countries cried loudest at the just-ended COP28 because they see monetary support as the only solution.

In the Global North where main polluting actors abound, except for Russia, India, China, Brazil, Australia, Japan, Saudi Arabia, which are not in the Global North, there are no benchmarks available to deal with skyrocketing emissions or cutting them down. In this regard, the main polluting actors like US, UK, German, France, Canada, among others, are acting instead of participating in real climate action.

Overall, climate action is not only threatened by political machinations from main global polluting nations but also governments in developing countries which stifle climate action in their own countries while blaming other countries for their mistakes, as if the world has no eyes or ears.

- Peter Makwanya is a climate change communicator. He writes in his personal capacity and can be contacted on: [email protected]