SOMETIMES artists go on a residency programme and produce the same kind of work they did before, using the same materials and techniques they have always done.

That would be a wasted opportunity for growth through experiment and inspiration in a new environment.

A trio of young female artists Lillian Magodi, Nothando Chiwanga and Shalom Kufakwatenzi recently completed a residency at Animal Farm Artists Residency, and hosted their anticipated exhibition titled Zvepano at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe (NGZ) in Harare.

Curator Laura Ganda says the residency was meant to challenge the artists, and take them out of their comfort zone in terms of exploring materiality, working with new forms and digging deeper into their existing practice.

The Shona exhibition title Zvepano can be read as an expression of detachment and letting go of anxiety over social, economic, or political issues that could be negatively affecting people.

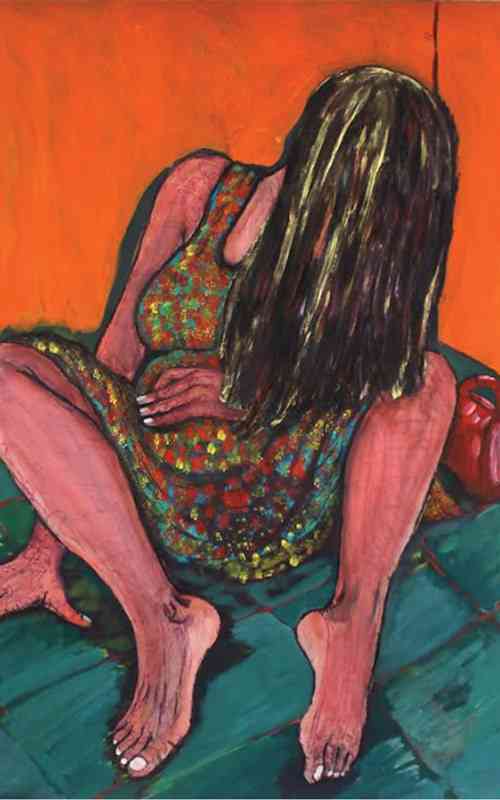

There is a pervasive tension in Magodi’s work, which might translate to some as sadness.

The absence of mirth may be interpreted as a conflicted condition.

“My work is about personal experiences and motherhood, and how it affected me mentally,”Magodi noted.

- Gweje relishes fashion achievements

- Daily life struggles reflected in Burning Figure

- 'Film sector drives economic growth'

- My Beautiful Home contest over subscribed

Keep Reading

In this exhibition Magodi attempts to balance her usually exclusive female subjects by including two portraits of a young man seated on a chair.

The majority of her work depicts women of various ages, with and without props, including babies.

One portrait depicts a child seated alone with a teddy bear abandoned by its side. In anticipation of adulthood the work is titled Kurauone, which literally means grow up and see.

The title and the work suggest that ignorance and innocence will pass, and adulthood brings challenges and difficulties. The title is also a traditional Shona name for a male child. The emotions in Magodi’s subject are betrayed by their posture.

A woman seated on the ground with her legs drawn to her body and the arms wrapped around her conveys suffering, pain and enduring trauma.

The artist sometimes hides the subject’s trauma by letting their hair fall over some of the faces, obscuring their facial expression. The subjects touch their own bodies in various ways that might be self-soothing.

While Magodi has often incorporated colour to her drawings, which might be an effort to lighten up the mood, her recent work shows her employing a vivid palette of more saturated hues.

She has also begun to incorporate painting and collage, which adds layers and depth to her exciting new work. A familiar motif in Chiwanga’s work is her dramatic staged self-portraits.

Her recent work rises to a new level by use of custom-made garments, and iconic choice of landscape. She stages herself wearing a multi-coloured dress made out of yellow satin and carries multiple kaleidoscopic patches including colourful braids.

As a stand-alone the piece is titled Rokwe Rangu which is a possessive term that simply means my dress. In reference to the eclectic garment, the artist explains: “This time I decided to venture into installation and recycled materials.”

The dress takes on more meaning, as it becomes an elaborate costume for the staged portraits.

In the images Chiwanga poses with extravagant gestures and much flair. The angle of the camera puts the viewer below the subject resulting in the elevation of her body like that of an ascending or descending deity.

The blue sky with white tufts of cloud and granite rock where she stands are the only visible elements that represent that which is above and that which is below (pasi nekudeka).

Her body symbolically connects the heavens and the earth.

In one image she breaks her own custom, to include a male figure posing with her thereby creating a new dynamic. The image titled Murudo Murudo speaks of a relationship between a man and a woman, and is critical in how it marks the evolution of the artist’s style and themes, going beyond simple props that can be easily manipulated.

The man’s presence complicates Chiwanga’s story and adds an interesting new angle to the narrative.

For Kufakwatenzi, her works include a riveting live performance at the official opening of the exhibition where her parents were in attendance. The rest of her work includes installations made from hessian fabric manipulated into different forms incorporating threads and textile.

Some parts of the work are twisted, and some are spherical, suggesting medicinal orbs made from rolled herbs.

Religious syncretism is a very clear implication in Kufakwatenzi’s work as she combines traditional material that is black with spots like the plumage of a guinea fowl, (hanga) with fabric used for church uniforms printed with Christian symbols and emblems denoting church denominations.

The artist said: “I have been working on a series called Tutundu (burdens) and during the residency I was focusing on spiritual baggage between indigenous cultures and (western) religion.”

Not all her work is loosely constructed because some pieces are hung onto frames that draw the eye inside.