IN Glen Norah, one of Harare’s oldest high-density suburbs, a responsible parent or guardian needs to juggle between granting a child the right to play or constantly keep a keen eye on possible dangers which may harm the young ones.

From ever busy roads, hard-hearted criminals and stray pets, the dusty streets are not the safest place for children. Glen Norah’s Kunzwi Street is no exception.

Tinashe Charika (31) and his wife have resolved to keep their hyperactive 18-month-old daughter confined in the house, much to the chagrin of the adventurous toddler.

“We are afraid of where our daughter may end up if we let her out of the house to play because people are dumping things everywhere, including used diapers, right in front of our house,” the father of one told NewsDay while carrying his offspring.

Just outside the precast wall surrounding his rented accommodation lies a huge heap of garbage as fellow residents have turned this corner into a dumpsite.

“We are immensely affected as a family because apart from constantly restraining our child from going out, we have to avoid the waste getting into our household and also survive the odour that the waste discharges into the atmosphere,” said Charika, who fears the worst could be on the horizon as the summer season approaches.

The garbage dumpsite is teeming with disease-spreading vectors such as flies and rats, while harbouring pathogens that promote the spread of such diseases as cholera, typhoid, dysentery and malaria.

- Chamisa party defiant after ban

- New framework to tackle IPPs’ hurdles

- Harare residents threaten mass protests against Pomona deal

- Chamisa party defiant after ban

Keep Reading

In Harare, a concoction of poor waste management, unreliable public water supply and burst sewage pipes among other public service delivery shortcomings has necessitated a recurrence of diseases, including the dreaded cholera which killed more than 4 000 and affected close to 100 000 others in 2008 and 2009.

Earlier this month, authorities in Harare announced yet another cholera outbreak.

Cholera, a severe intestinal infection caused by ingesting food or water contaminated with the cholera virus, is one of those diseases which Charika and family dread.

“The city would like to inform residents that it has now five confirmed cholera cases in Hopley Zone 5, Stoneridge, Southlands, Granary and Adbernie Mbare,” City of Harare wrote in a statement while urging “residents in affected areas and Greater Harare to take necessary precautions to avoid contracting cholera,” the council said in a recent notice to residents.

For Charika and his neighbours who have to endure the slimy and pungent stench-emitting dumpsite, the areas where the disease has been recorded are too close for comfort.

Despite the red alert, most residents in Harare’s crowded high-density suburbs seem to care less.

“When we dump waste on the roadside, it is not by choice, but because the authorities are not coming to collect bins,” says Rejoice Mapira, one of Charika’s neighbours.

Similarly, the majority of residents across the city are clueless on how to safely dispose of waste and so they end up burning or dumping it in open spaces.

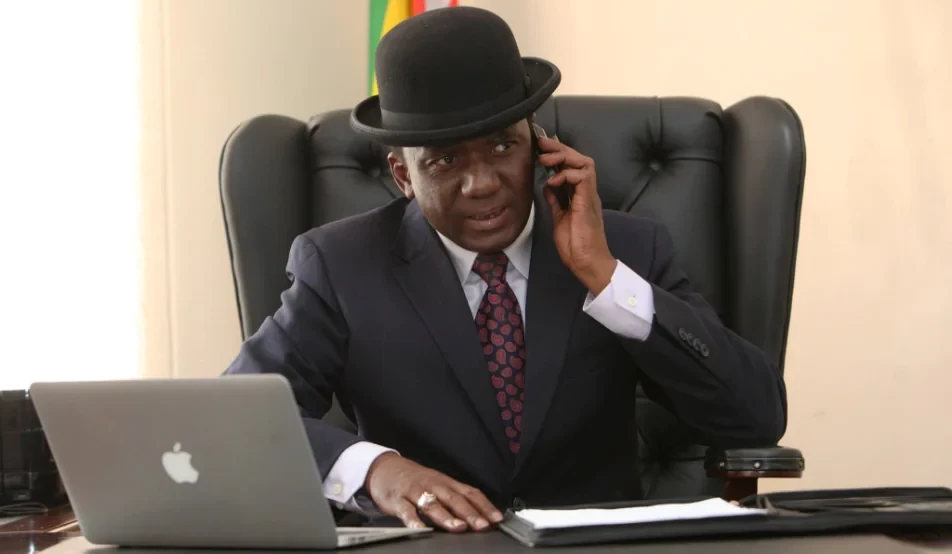

“Council should ensure weekly or even fortnightly collections but before that they must ensure that this heap is cleared and perhaps people will be shy to dump,” Mapira suggests. President Emmerson Mnangagwa has decreed a three-month-long state of disaster in the Harare Metropolitan province to help clean the city.

Through a notice titled State of Disaster: Emergency Solid Waste Management, Mnangagwa said Harare was “littered with waste dumps, accumulating in business and residential areas and open burning of garbage and indiscriminate illegal dumping of solid waste and littering”.

Mnangagwa, albeit making the declaration in the run-up to the August 23 and 24 harmonised elections to — in hindsight — ostensibly discredit opposition-run local authorities, seems to have failed to follow up his decree by investing in waste management infrastructure, human resources and efficient collection practices.

“This year we have engaged an additional 267 street cleaners particularly to clean the central business district and Mbare,” council’s environmental manager Lisben Chipfunde recently told a stakeholders meeting.

However, the exercise, which is yet to yield tangible results, seems to have eluded most populous high-density suburbs where residents are daily struggling with garbage as well as its negative effects.

“We are in a perpetual state of disaster here (and) there is no one to confront. We have also joined the dumping so it now feels normal but hopefully there will be an intervention soon,” said Charika, who admits he will soon relocate to protect his family if the situation persists.

While Section 73 of Zimbabwe’s Constitution emphasises that every person has “the right to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being”, authorities have robbed Charika and his family of that right to a humane environment.

While adjusting his grip on his daughter and pointing to the rotting dump he resignedly says: “I am not confident that this will be over any time soon because we have stayed here for almosta year and I have not seen this heap of waste cleared even once.” Zimbabwe has recorded 108 suspected cholera deaths and 5 030 new cases with the latest health ministry situational report indicating that there are 55 new suspected cases and one death recorded by Monday this week.

According to the report, 41 districts across the country have reported the outbreak, with Buhera and Gutu recording the highest number of cases.

Harare has 155 recorded cases of cholera but no deaths.