GREG SHAW is an established figure in Zimbabwe’s art community and brings much needed diversity to the scene.

His Grey-zones exhibition at Artillery Gallery in Harare touches on rare themes which have wide implications.

Shaw’s monochromatic works cast an ominous shadow on the exhibition, laying a gray pall like the aftermath of a battlefield. It is a radical contrast to a most recent show at the same venue, Kombo Chapfika’s TDLR, which popped with colour.

Shaw’s invasion of the space transforms the white walled space into a funerary sanctuary.

Although gray is the dominant colour, it is not all there. Frontier (oil and wire on canvas), Manifesto (soil, wire and paper on canvas), Nyaure Batea (soil, mercury, oil and wire on paper) and Sentinel (oil, soil and wire on canvas and wood) have vivid and earthy hues that radiate from natural pigments.

The exhibition includes three-dimensional works such as Carving Line (cow horn, wire, bitumen and charcoal on paper), War Table (horns and bitumen on steel), Fence ( steel), Nine Buckets (steel, cow horn, wire, charcoal on printed maps), and Before the Law (cow hooves, clay, wood, wire on steel).

“The exhibition is an interrogation into borders and border-theory,” he told NewsDay Life & Style.

He describes the story behind his works as reality of the natural world with its incumbent threats and how the sense of the individual is reduced to the inward, personal, and isolated being.

- Mugabe’s art: A celebration of African childhood

- Nyandoro envisions a beautiful life for women

- Grey-zones speaks for the unseen

Keep Reading

In erudite statements smattering the white walls of the exhibition space, the artist expounds on concepts behind the artworks so thoroughly that at times the viewer might be overwhelmed by the demand for comprehension.

He writes about the relationship between the State and its citizens, availability of socio-economic structures that provide access to resources, and hierarchies of power, and the mechanisms hidden behind these structures.

Inspired artists frequently communicate insights that are beyond their normal perceptions. On a purely cognitive level the concepts and symbolisms in the exhibition resonate beyond the artist’s deliberate intentions, and articulated texts.

Created by using soil, hooves, wood, razor wire, and etching the artworks also highlight the existential ennui of lying in limbo, in-between territories, in the breadth of a border, which does not serve as immediate conduit.

Such a situation can result in feelings of alienation and trauma associated with the outsider, which is how Shaw describes himself in a series of self-portraits titled Outsider Series I-IV.

The in-between world can be characterised as a demographic that is generally ignored and overlooked.

It reflects on uncommon issues, which due to their lack of “colour” make them neither appealing nor distasteful enough to engage public consciousness and become part of popular discourse.

In Shaw’s body of works made by etchings, a sense of trauma can be acutely felt. Etching seems to be a laborious and meditative process which lends a deeper and lasting impression.

Levels of Life shows six naked male figures sprawled in different positions on the ground as if they were cast down from heaven.

The bodies look grotesque deformed and skeletal. Their lack of joy or their terror is suggestive of a deep soul-searching for an elusive answer to life’s hardest questions.

Ordinary Survivor is a naked figure who might be a bald old woman of very old man with sagging flesh.

The figure has a gaping mouth and rings around the eyes combining to conjure almost unimaginable trauma.

The gap on the chic suggests hollowness inside, which is ghoulish considering the unshapely bloated figure. It is a sobering thought considering that the suggestion is that it is the “ordinary” in this case.

The Sentinel looks like an abstract sculpture made from scrap metal. There is a suggestion of fists and unkempt hair.

It is comforting to see how this raggedy sentinel resolutely stands guard over the unseen traumatised lot.

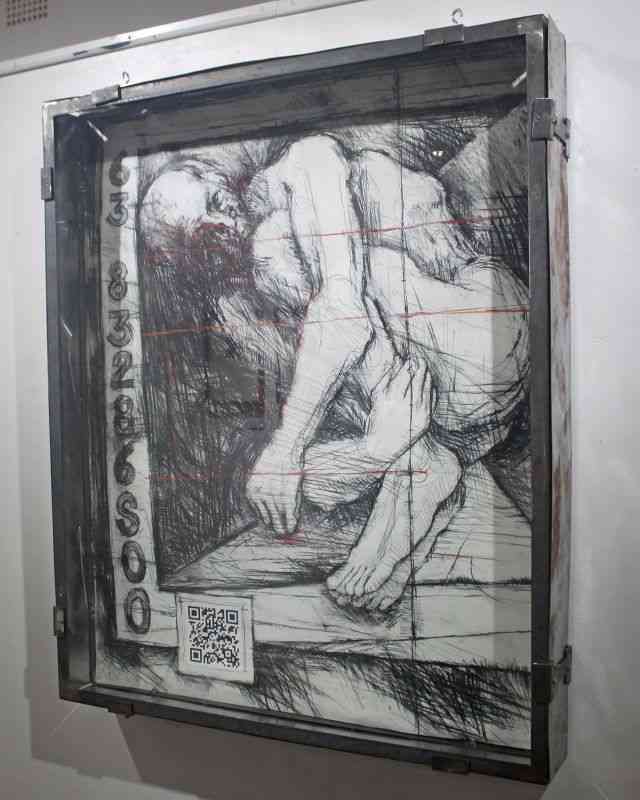

A vulnerable elderly man in fetal position seems to peek sullenly in the sad picture titled Captive.

The Zimbabwean national identity card serial number marked on the side references the artist and makes it a self-portrait, which the artist might rather call it Self ID as the label on another series of his self-portraits.

The iron and glass casing in which the artwork is framed emphasises the notion of captivity, adding an element of being exhibited like a tortured animal.

The caged and afflicted individual becomes a prisoner in Passenger 1 and Passenger 2 where the steel and glass frame is overlaid with barbed wire.

Here the trauma is elevated to an unforeseen level. There is no relief and the situation becomes chronic.

The inverted figure is disorienting for the viewer in a way which induces vertigo and may cause loss of balance, which might imply the emotions being experienced by the subject.

Shaw’s etchings can be deconstructed to speak for those who are living in a private hell, silent agony and suffering in solitude.

Stripped of their clothes, the subjects’ lack of cover, superficial status and false impression makes those in similar circumstances feel seen.