ZIMBABWE is turning 44. At some point, it will be 50, then 100.

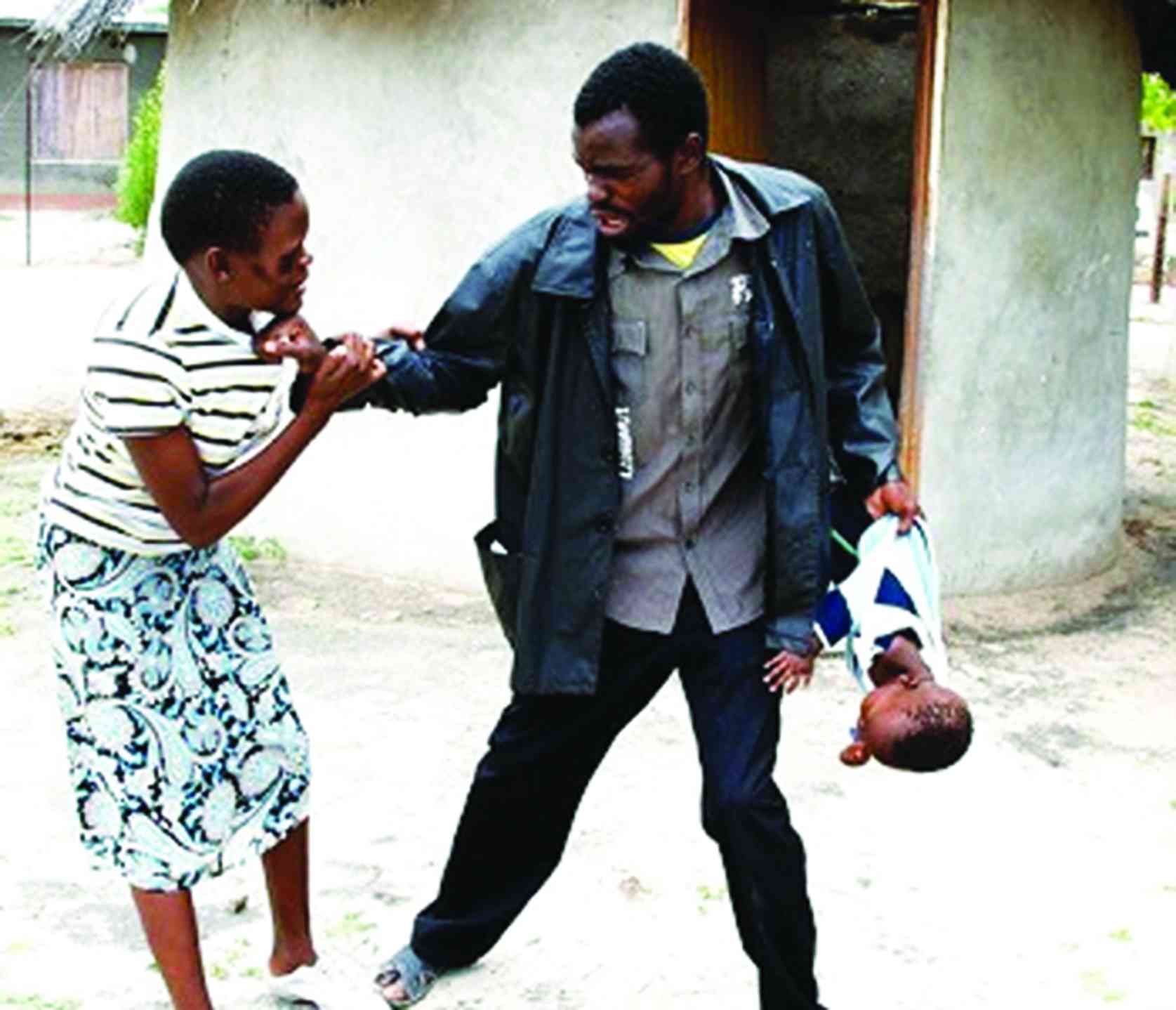

What does this mean for the people of Zimbabwe? A walk through Harare paints a picture that fills one with revulsion, shame and anger.

The city is beyond filthy and beyond chaos. The capital city of this proud republic exists in a near post-apocalyptic state.

People drink, urinate and defecate in the streets. Cars are driven with crazed abandon; half of the pavement space is taken up by bellicose vendors. Anything goes in Harare.

The other day, a car driving against traffic in Chinhoyi Street did not even bother to stop at an intersection and, as expected, it hit another vehicle driving down Jason Moyo Avenue.

We all stood around and laughed at the spectacle, but it was about par for the average Harare day.

How did it come to this? The whites who ran the city pre-independence were not half as educated as the people who have gleefully run down the city.

They were not even half as many either. The answer is perhaps to be had in an exchange I had with a student at one of our many tertiary institutions.

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Bulls to charge into Zimbabwe gold stocks

- Ndiraya concerned as goals dry up

- Letters: How solar power is transforming African farms

Keep Reading

I was invigilating an examination; the deputy registrar of the university had issued instructions that none of the students were to use the toilets before the start of the examination.

This was done to stop them from secreting bits of paper with notes on them in the rest rooms.

We passed on this information to the students as we turned them away. Most of them listened and sought an alternative.

But a particularly pugnacious gentleman would not countenance this; he pushed past us. His words were an eye opener.

He snarled: “We did away with such oppression when we got rid of the whites!”

To this gentleman, abiding by a simple rule, instruction or law is a white thing and is an injustice. This was epiphanous and that single moment captured what is wrong with our sorry country.

The unrecognised challenge that fell on the shoulders of our leaders and us as a people on April 18, 1980 was to define independence. Unfortunately, nobody did so.

Independence came to mean the rejection, bristling with pride, of all things white or Western. Nobody recognised what a terrible responsibility we took upon ourselves. We assumed then the reins of governance and the responsibility for the future which is the shambolic Harare of today buoyed by the misplaced confidence only the simpleton knows.

The challenge was then, and still is, to define independence in a positive and active sense: As a set of values, aspirations and actions, not negatively as a mere rambunctious rejection of all things Western.

Independence should not have been defined in the negative and oppressively passive sense of things we no longer had to do because finally after 84 years our destiny was in our own hands.

Instead, independence should have been defined in terms of a set of prescriptions and responsibilities. That is things that needed to be done.

This would imply us being masters of our own destiny instead of being carried along passively by destiny as we are being done today.

Our default reasoning today seems to be to just leave things in free fall until they can fall no more.

It is no coincidence that most corruption is colloquially described as kuita chivanhu in the Shona vernacular.

The implication is that this accommodative and mutually beneficial soft crime is the African way of doing things. The straight laced hard-nosed way is European.

As Africans we really do believe that all these rules and regulations are a hindrance.

It is understandable because our relatively unsophisticated societies had not needed the widespread codification of social mores.

After all at independence most of us had living relatives who had been born in pre-colonial Zimbabwe in other words in the Early to Middle Iron Age societies.

There was no tradition in us of the formalised administration of complex societies.

Governance is an activity. It is neither passive nor selective. It takes place in nondescript offices run by anonymous bureaucrats attending to a thousand minute details day in and day out.

It is about doing the little things well and fastidiously; each and everyone, everyday.

Today, nobody wants to enforce a thousand traffic regulations or city by-laws. All things seem so unimportant to our eyes. This is where we have not only failed as a nation but continue to fail ourselves.

Any hopes of a revival for Zimbabwe lies in us understanding that we have an onerous responsibility on our hands.

That independence was and is a call for all hands on deck and not a great big holiday from the tedium of governance.

Independence should never have become this surreal free for all wherein everybody does whatever they want, wherever and however.

But a call for us to do all things that held this country together and made it make sense.

After all the country is the same, the people who did all the work that made the country tick are the same.

The only change has been in the leadership and the culture it brought in in 1980.

We need to change how we perceive independence. The whites by enforcing all those laws and regulations were not being malicious.

It was and is what is needed in order to hold any large and complex society together.

So, as we celebrate independence again, let us shame ourselves with the past 44 years of mediocrity.

Let us be brutally honest with ourselves and admit that we, as a people, as a socio-political philosophy, are what is wrong with this country. We need to fix it.

Ignatius Tsuro is a commentator on social and political issues. He writes in his personal capacity.