THE central conundrum of democracy in a pluralistic society is tolerance.

Citizens and leaders in democracies must protect the full political rights of expression and political involvement of groups they find unpleasant if they are to practice political tolerance. It has long been known that liberal democracies must include tolerance as a key component.

The degree to which people are receptive to and prepared to make allowances for others who are different from them is frequently seen as a marker of a strong and functioning liberal democracy, however, the bounds of tolerance are controversial. Nevertheless, gaining political tolerance is difficult, not least because individuals are innately intolerant.

Lack of political tolerance has created an uneven playing field, which has reduced the room for vulnerable groups like civil society, women and youths who are still trying to enter the political sphere.

Extreme political intolerance, which led to political violence and egregious human rights violations, has stained Zimbabwe’s history both before and after independence. The pervasive culture of political intolerance in Zimbabwe is ingrained not only in the media, but also in important State institutions and political parties from all sides of the political spectrum.

Within intra-party democracy, there is a high prevalence of political violence and intolerance, which is a mirror of society’s overall polarisation and division. When political leaders employ violence, it conveys a message that using violence to further political goals is acceptable. As a result, violence in society continues to be normalised, which has serious negative effects on a nation’s stability and general well-being.

Hate speech motivated by animosity for opposing viewpoints is at the heart of the pervasive political intolerance in Zimbabwe. In addition to formal and informal statements made by some Zanu PF party leaders, its members and supporters, hate speech also comes from the main opposition Citizens Coalition for Change.

A good indicator of democracy, constitutionality and societal peace is tolerance, which can be tested through social discussion. However, violence-fuelled hate speech has been used to counter elections, protests and fundamental freedoms of expression, which are important components of social discussion.

- Fostering political tolerance culture in Zim

Keep Reading

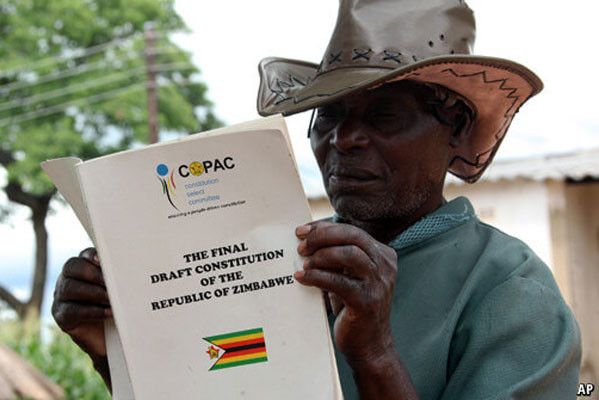

Even though the Constitution has clauses to control bigotry and hate speech, the political landscape is rife with it. The main causes of hate speech in Zimbabwe are political intolerance and intolerance for opposing viewpoints, both of which are motivated by political expediency. As a result, Zimbabweans are binary characterised.

In turn, impunity encourages hate speech, creating a vicious circle of intolerance. Senior government officials, who openly and unaccountably encourage hate speech, are at the forefront of it. One way they do this is to characterise the opposition as an adversary, a terrorist group and an existential threat that tries to undo the victories of the liberation struggle.

As a result, the political class in Zimbabwe views political rivalry with distrust and open animosity. To build lasting peace in Zimbabwe, a culture of political tolerance must be ingrained. Political interaction and will are necessary for political tolerance. The main players should engage different political groups in peace talks and other peace-promotion activities such as organised physical peace engagement sessions to combat political intolerance.

It is unacceptable for political violence and intolerance to persist in Zimbabwe’s democratic system. For a democratic and peaceful society to be built, the populace must demand more from their leaders and cooperate.

The conflict between fostering internal democracy and upholding party discipline is one that most political parties must contend with. Parties should be able to foster an atmosphere whereby members may come together around shared principles, while also being free to voice their opinions about party performance, structures and policies.

The only way for progress to be made is via vigorous debate. A culture of tolerance must also have certain essential components, such as education. Tolerance among citizens can be fostered by political engagement and education.

By immersing citizens in the democratic process and safeguarding the civil freedoms of all groups, States can support general democratic learning and stability. Additionally, improving freedom of expression is necessary. Political tolerance is hampered in a society where freedom of expression is not protected. A culture of tolerance fosters and makes possible open discourse and a range of political viewpoints.

A culture of tolerance can be developed with the help of the media. States have a responsibility to promote a pluralistic media landscape that presents a range of opposing viewpoints. The use of negative reporting by State-controlled media has been criticised and is allegedly still happening.

It is also asserted that over time, our Parliament has passed several legislations which have impeded journalists’ freedom of expression and complicated their work. Building an equal and non-discriminatory atmosphere through the promotion of a diverse range of ideas and views among people and institutions improves political life.

Political supporters and leaders must also treat everyone as their neighbour. Everything changes when you redefine them as a neighbour rather than a political rival. In other words, whatever your disagreements, you should not do anything harmful to them as you shall continue to be neighbours after elections. Political parties and leaders come and go.

In advanced nations, people may quarrel during elections, but afterward, everyone comes together to build their nation. This is what Zimbabwe has to emulate. Being tolerant is one of the most challenging things that people have to do in a society. Most likely, tolerance is a quality that we must acquire. Politicians are expected, and rightfully so, to set an example for the people as their representatives.

Artwell Dzobo is a researcher. He is an international relations graduate from Africa University and writes here in his personal capacity.