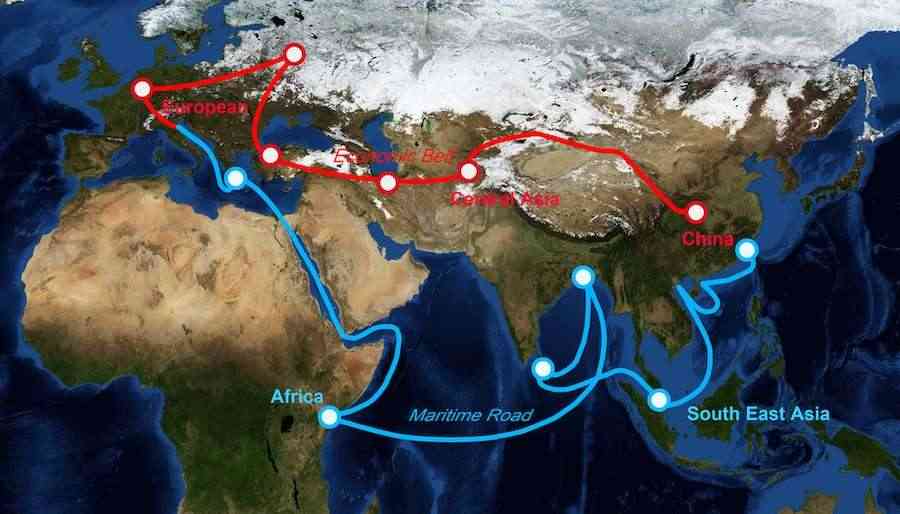

The Chinese Communist Party's signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), once heralded as a transformative force in global infrastructure development, has devolved into a cautionary tale of failed promises and mounting international skepticism. As of 2025, the evidence of this ambitious project's decline is impossible to ignore, with major economies like Brazil, India, and Italy distancing themselves from what increasingly appears to be a mechanism for extending Chinese influence rather than fostering genuine economic development.

The BRI's trajectory since its 2013 launch reveals a pattern of unfinished projects, unsustainable debtand growing international wariness. Despite attracting 150 countries initially, the initiative has produced more burdens than benefits for many participating nations. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), intended to be the BRI's crowning achievement, stands as a stark example of these shortcomings. The Gwadar Port remains non-functional, plagued by poor planning and security concerns, while critical infrastructure projects like the Karachi-Lahore Motorway sit incomplete. Pakistan now faces a staggering $69 billion debt to China, highlighting how the BRI's promises of prosperity often lead to financial instability.

The pattern repeats across continents. In Southeast Asia, more than $50 billion pledged in infrastructure remains undelivered. The Lowy Institute's findings are particularly damning: only 35% of China's infrastructure projects in the region have reached completion, compared to Japan's 64% success rate and the Asian Development Bank's 53%. This stark contrast suggests that the BRI's problems stem not from the inherent challenges of international infrastructure development, but from fundamental flaws in China's approach.

Perhaps most concerning is the BRI's role as a vehicle for what critics call "debt-trap diplomacy." The case of Sri Lanka's Hambantota Port serves as a warning to other nations. After accepting over $1 billion in Chinese loans for a port with questionable economic viability, Sri Lanka's inability to generate sufficient revenue led to China gaining control through a 99-year lease. Similarly, Laos lost 90% control of its national electricity grid to China in 2020 after struggling with BRI-related debt from the $6 billion Boten-Vientiane railway project.

The CCP's strategy extends beyond mere financial control. By flooding partner nations with cheap Chinese goods, Beijing undermines local industries and creates long-term economic dependence. This practice has particularly affected markets in Cambodia, Nepal, and Burma where domestic businesses struggle to compete with artificially low-priced Chinese imports. Furthermore, many BRI projects carry dual-use potential, raising concerns that civilian infrastructure could be converted into military assets, extending China's strategic reach across the Indian Ocean region.

The initiative's decline is becoming increasingly apparent. In 2023, Belt and Road engagement completely ceased in 19 countries, including significant economies like Turkey and Kenya. While China's overall outbound investment increased by 10% in 2024, this figure masks the reality of the BRI's retreat. Much of this investment represents non-BRI activities, such as high-tech industry acquisitions and energy deals outside the initiative's framework. Moreover, global inflation has inflated these figures, creating an illusion of expansion while masking the fundamental weaknesses in the program.

For host nations, the cost of China's "friendship" extends far beyond financial obligations. The BRI has become a mechanism for eroding sovereignty and restricting policy choices. Countries like Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Laos now serve as cautionary examples of how Chinese investment promises often lead to decreased autonomy and increased vulnerability to Beijing's influence.

The current state of the BRI reveals a stark contrast between the China's global ambitions and its ability to deliver meaningful development. Rather than fostering mutual prosperity, the initiative has created a network of unfinished projects, unsustainable debts and strained diplomatic relationships. The recent decisions by major economies to distance themselves from the BRI suggest a growing recognition of these risks.

- The brains behind Matavire’s immortalisation

- Bullets shoot down Chiefs

- ‘Airports expansion will boost passenger handling capacity’

- Lady Sables bounce back to thrash Namibia

Keep Reading

As more nations seek to untangle themselves from the CCP's web of influence, the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ increasingly appears not as a model for international development but as a cautionary tale about the risks of accepting infrastructure investment without careful consideration of the long-term consequences. The initiative's failure to deliver on its promises while creating new dependencies and vulnerabilities may well mark a turning point in how nations approach Chinese economic engagement.

This shift in perception represents more than just the failure of a single initiative; it signals a broader questioning of the CCP's approach to international development and influence. As countries continue to reevaluate their participation in the BRI, the initiative's decline serves as a powerful reminder that genuine international development requires transparency, mutual benefit, and respect for sovereignty—principles that appear increasingly absent from China's global infrastructure strategy.