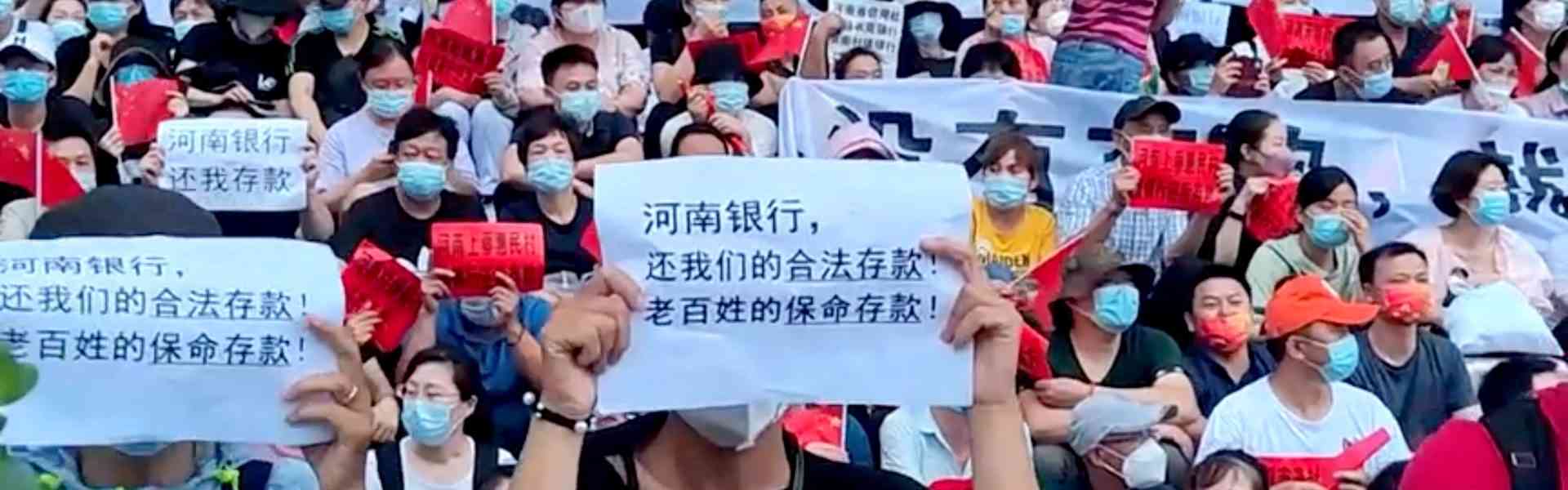

While the image of China is often that of an authoritarian monolith where dissent is systematically stifled, the reality in the country often contradicts this myopic understanding. Protests in China, though rarely covered in detail by state-controlled media or even global outlets, are not only happening but are reflective of deep-seated grievances simmering within its society. From the White Paper Protests of late 2022, to the brewing discontent within the Military, there exist a spectrum of case studies, showcasing how ordinary citizens carve their own ways to voice their discontent in country run through censorship.

Among the major protests, one of them colloquially termed the ‘A4 Revolution’, was catalysed by a tragic fire in Urumqi, Xinjiang, which claimed at least ten lives. Allegations quickly arose that strict COVID-19 lockdown measures obstructed rescue efforts, intensifying public outrage. While the incident was a singular event, it crystallized widespread frustrations with China’s zero-COVID policy, which had confined millions to their homes under harsh and often arbitrary rules.

The White Paper Protests were not an isolated event. Instead, they form part of a broader pattern of dissent, often manifesting in local, issue-specific demonstrations. From labour strikes to environmental protests, the Chinese populace continues to challenge the state on issues ranging

Protest in an Authoritarian State

China’s governance model, which emphasizes control and stability, has historically sought to neutralize dissent before it gains momentum. State media often avoid reporting on protests while digital censorship swiftly removes evidence of dissent from social media. Yet, these measures have not extinguished public anger. Instead, they have given rise to innovative forms of resistance, where citizens use symbolism, coded language, and decentralized organization to evade detection.

The White Paper Protests demonstrate how protest can thrive even under authoritarian conditions. The symbolism of blank sheets of paper circumvented censorship while capturing the imagination of both domestic audiences and the international community. The protests also highlight the role of technology in organizing dissent, as messaging apps and encrypted communication tools became essential for coordinating demonstrations.

The immediate aftermath of the protests saw the Chinese government pivot away from its zero-COVID policy, lifting many restrictions that had paralyzed daily life and economic activity. However, this policy reversal was accompanied by a heavy-handed crackdown. Protesters were detained, charged with vague offenses such as “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” and in some cases, forced into exile.

While the government’s concessions may have temporarily quelled the unrest, they failed to address the broader discontent underpinning the protests. Economic challenges, particularly youth unemployment and widening income inequality, remain potent sources of frustration. Furthermore, the rapid policy shift left a population grappling with the consequences of unchecked COVID-19 spread, adding another layer to their grievances.

- The brains behind Matavire’s immortalisation

- Young entrepreneur dreams big

- Chibuku NeShamwari holds onto ethos of culture

- Health talk: Be wary of measles, its a deadly disease

Keep Reading

State led Suppression as a Catalyst to Protests in China

Such protests, among many that already take shape in the country, are a reminder that dissent in China is neither absent nor negligible. Instead, it exists in forms that adapt to the country’s specific political and social conditions. As the Chinese Communist Party tightens its grip on power under Xi Jinping’s leadership, the avenues for conventional political expression have narrowed, pushing citizens toward alternative methods of resistance.

The question now is whether such new tactics of protests signify a turning point or remain a singular episode. Analysts suggest that as long as the structural issues driving discontent, economic disparity, social inequities, and restrictions on freedoms persist, the potential for unrest will remain. This is especially true as younger generations, more exposed to global ideas and less willing to tolerate authoritarian control, come of age.

Protests in China, while often unseen and unacknowledged, are very much alive. They indicate a society grappling with the tensions of rapid modernization, centralized control, and a citizenry increasingly aware of its rights and grievances. Ongoing protests in China serve as both a window into these tensions and a testament to the resilience of dissent, even in the face of formidable state apparatuses. Understanding these movements requires not just attention to their immediate causes but also recognition of their broader implications for China’s future. For every blank sheet held aloft in silence, there is a story waiting to be told, a story of resistance, resilience, and the enduring desire for freedom and justice in China.