Farmer Zephaniah Moyo recounts how he once hurled stones at nighttime intruders on his patch of land in Zimbabwe.

Confronted by a group of elephants, the 54-year-old was never that confident in the solution. But the David versus Goliath stand reflected his desperation.

The horror of nocturnal visitors from neighbouring forests feasting on his crops has become a frightening reality for him. And that also goes for his two wives and 13 children.

Moyo produces maize and sorghum on his medium-sized plot, which gives him two metric tonnes of the staple at the end of every cropping season.

His farm is in Dete, a semi-arid area in Zimbabwe’s wildlife-rich Matabeleland North province.

His village borders a game park that is home to the country’s largest elephant herd.

Keep Reading

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Bulls to charge into Zimbabwe gold stocks

- Ndiraya concerned as goals dry up

- Letters: How solar power is transforming African farms

Just months ago, four elephants paid the family a visit and helped themselves to their maize crop.

“When they start eating your crop, they become very stubborn when you try to drive them away especially if you are not armed,” Moyo said.

On that night he chose to confront the elephants, he armed himself with stones, a catapult and a torch to try to chase the crop raiders away — with his family in support.

“I showed a torch ... and shot one of them with a catapult. I was relieved that they walked away without charging at us,” he said.

Moyo said elephants often get frightened by the torchlight, as torches are often used by poachers.

Although Moyo won the battle that night, the elephants had already helped themselves to nearly half his crop.

“The elephants are now as good as being part of my big family as they are competing for food with my children,” he said ruefully.

Moyo’s anguish is shared by Lovemore Ndlovu, a neighbour with 11 children.

Ndlovu (52) speaks of the lions and hyenas that attack livestock, as well as the baboons that raid maize granaries.

In response to the depletion of grazing lands, authorities removed the game park fence so that cattle can graze inside the park.

"Three elephants entered my sorghum field in May this year. We tried to call CAMPFIRE but they only came three hours later,” he said, referring to the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources.

“By then, the elephants had cleared everything. I have no one to turn to for my children’s food. Even more painful is that we have no compensation even when it is evident we have lost our crops to elephants. What will my children eat?”

To repel the problem of animals, villagers in the area spend sleepless nights guarding their crops until the end of the harvesting season.

Villagers are not allowed to kill the elephants, which often retreat into the forest after feasting on the crops.

The plight of Moyo and Ndlovu is typical for the villages bordering game parks. When the animals fail to get enough to feed, they trespass into the villages, where residents are sometimes trampled in encounters.

With nearly 93 000 elephants, according to the last countrywide elephant census in 2014, Zimbabwe has the world’s second-largest population after Botswana, and about a quarter of Africa’s elephants.

Sixty Zimbabweans were reportedly killed by elephants in the first five months of the year.

Bearing the brunt

Villagers who bear the brunt of the conflict have accused safari operators of using salt to lure elephants from the forests to come closer to human settlements where they can be viewed by tourists.

But once they are done with the viewing, the animals become the burden of villagers.

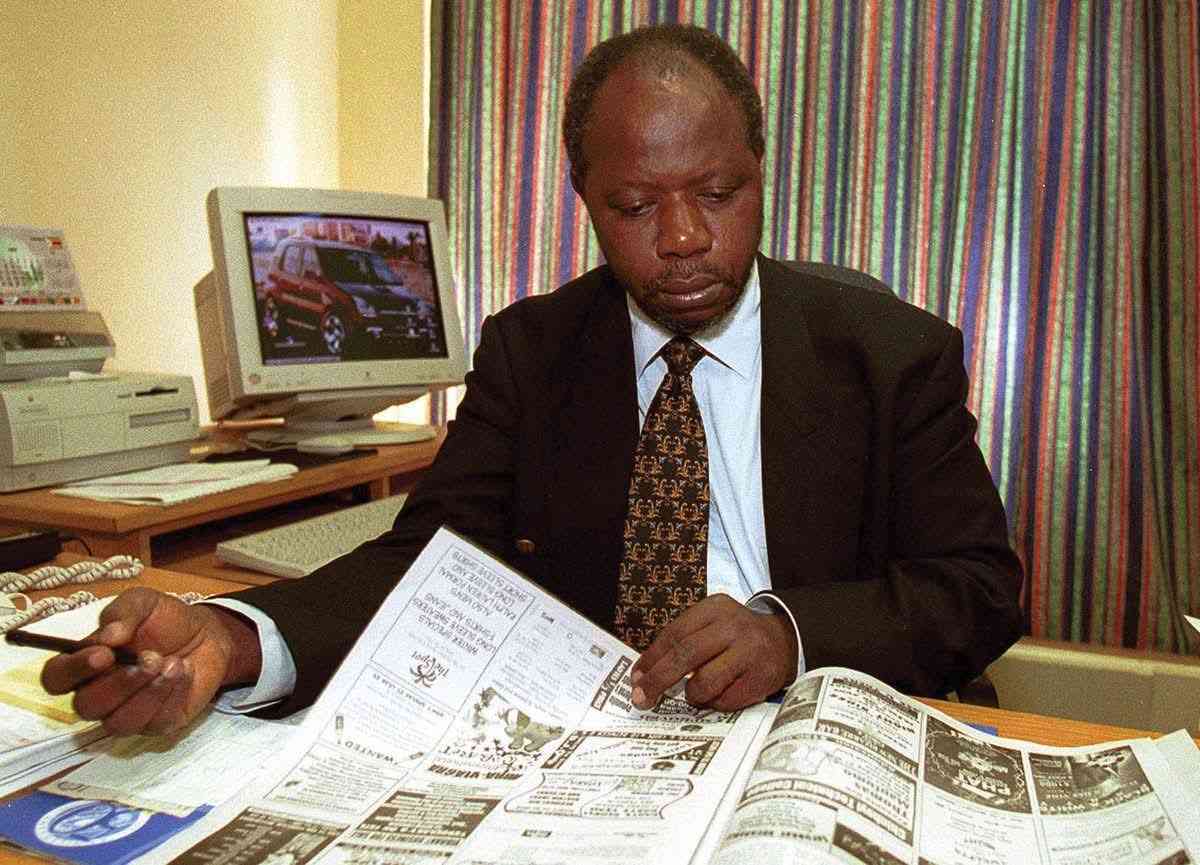

Emmanuel Fundira, president of the Safari Operators Association of Zimbabwe, disputes this claim.

Fundira said the problem is caused by people settling into animal habits. “It is the people themselves who encroach and start giving themselves land in animal areas,” he said.

Fundira said Dete, where Moyo and Ndlovu live, with many more other families, was largely reserved for safari operations.

He said operators have, instead, built waterholes within animal habitats for them to drink and it is often in those places that visitors watch the animals.

Conservationist Ndlelende Ncube said: “While indeed humans are justifiably concerned about the elephant menace, let’s also work on methods that do not cause harm to elephants. If we continue killing elephants, we risk them becoming extinct.”

Ncube, director for Tikobane Trust, which works to prevent conflict between people and wildlife, said people should use repellents to deter the elephants.

Environment, Climate and Tourism minister Mangaliso Ndlovu said growth in human and elephant populations is worsening the problem.

“In 1980, our population in Zimbabwe was nine million and 48 000 elephants. We have since increased now to 16 million, while the elephant population has also doubled to 94 000,” the minister said.

Ndlovu said the country has no policies to compensate those who would have lost lives, crops or livestock through human-animal conflicts.