By Clayton Besaw

THE insurrection at the US Capitol on January 6 shocked Americans and the world. But the US was not alone in its rocky transfer of power: Last year saw more election-related violence than any year in the past four decades.

At least 44% of national elections that took place in 2020 had some form of violence, according to a new election violence database my team of conflict analysts released in 2021.

That is 33 national votes marred by violence.

Election violence is a type of political violence that seeks to unduly influence the process and outcome of a vote.

Attacks can be perpetrated by governments or civilians, against electoral infrastructure, political parties or voters.

Our database tracks all incidents of election violence going back to 1975.

Until last year, the worst year was 1990, when violence occurred in around 46% of elections.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The median annual rate dating back to 1975 is 30%.

How will 2021 stack up?

Countries to watch

So far, this year looks to be slightly more peaceful than last.

Of 42 national elections scheduled to occur in 2021, our data forecasts that roughly 40% are at high risk of violence.

Chad, Ethiopia and Haiti are at the most risk for election-related violence this year.

Chile, a generally stable democracy, is also unusually high on the list after a year of civil unrest.

Why these countries?

Though the causes of election violence are complex and unique to each country, my research finds many places that experience election violence share the same five characteristics: a history of election violence (indicating violence is “normalised”), high coup risk (an indicator of a weak State), high infant mortality rate (an indicator of a weak State), pervasive political violence (an indicator of a weak State), low gross domestic product (indicating a struggling economy).

When all five characteristics are present, our early warning forecaster raises red flags.

How we predict violence

The national data we processed finds that countries with longer and more recent histories of election violence are at risk of more violence.

The presence of other kinds of political violence — terrorism or civil war, for example – also increases the risk of election violence because political attacks can come to be seen as “normal.”

The government’s ability to exercise power is another important factor in election violence risk.

That’s because authorities in weak States usually cannot physically stop clashes — even if, as was the case in Kenya’s 2007 election, they can reasonably foresee conflict erupting.

History shows a weak government may also inflict election violence if the incumbent fears losing political power.

That’s what Azerbaijan’s president did in 2005 when growing political opposition threatened his leadership before the election.

To measure State capacity, we consider infant mortality rate, gross domestic product and the risk of regime change.

These factors show the government’s ability to maintain stability and promote well-being, which are reliable indicators of its power.

Election violence in democracies

The data shows that election violence in both democracies and non-democracies is increasing at similar rates worldwide — though the violence plays out differently, and occurs for different reasons.

In democracies, election violence can occur because of bitter partisan competition or as a result of political violence becoming normalised.

An incumbent leader who directly or indirectly encourages violence to suppress the opposition can also catalyse violence.

Former US President Donald Trump did this before and after the United States’ 2020 election, which led to the Capitol riot that killed five people.

In Nigeria’s 2011 presidential election, over 800 people were killed by violent mobs when candidate Muhammadu Buhari refused to concede defeat.

His denial of election results exacerbated pre-existing religious and regional tensions between the north and south.

Election violence undermines the legitimacy of a country’s political system.

By reducing voter confidence in peaceful democratic transition, it can eventually result in a shift toward more authoritarian governance.

Violence in authoritarian regimes

In places that already have authoritarian governments, bloodshed during election season isn’t a surprise.

Often, it’s an organised strategy used to keep votes from being free and fair — part of the broader toolkit that many autocratic leaders use to repress and manipulate the citizenry.

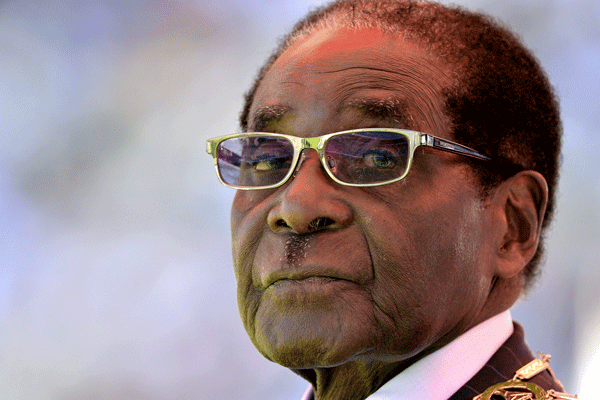

Zimbabwe and Belarus are useful examples.

During the late former President Robert Mugabe’s 37-year rule of Zimbabwe, for example, his Zanu PF party allowed opposition candidates to run for office — but regularly used violence to neutralise and intimidate the electoral opposition.

Even after Mugabe’s ouster in a 2017 coup, the country’s new rulers continued this strategy.

The August 2020 Belarusian presidential election saw embattled President Victor Lukashenko use similar tactics to declare his win.

Opposition candidates and party members were arrested and threatened in the lead-up to the highly contested August election, spurring massive protests.

Election-related violence will persist for the foreseeable future. In democracies and non-democracies alike, strategic attacks serve those who have power and want to keep it.