It is too early to assess the economic impact of this month’s highly-effective shutdown and the government’s heavy-handed response.

Guest Column: Anthony Hawkins

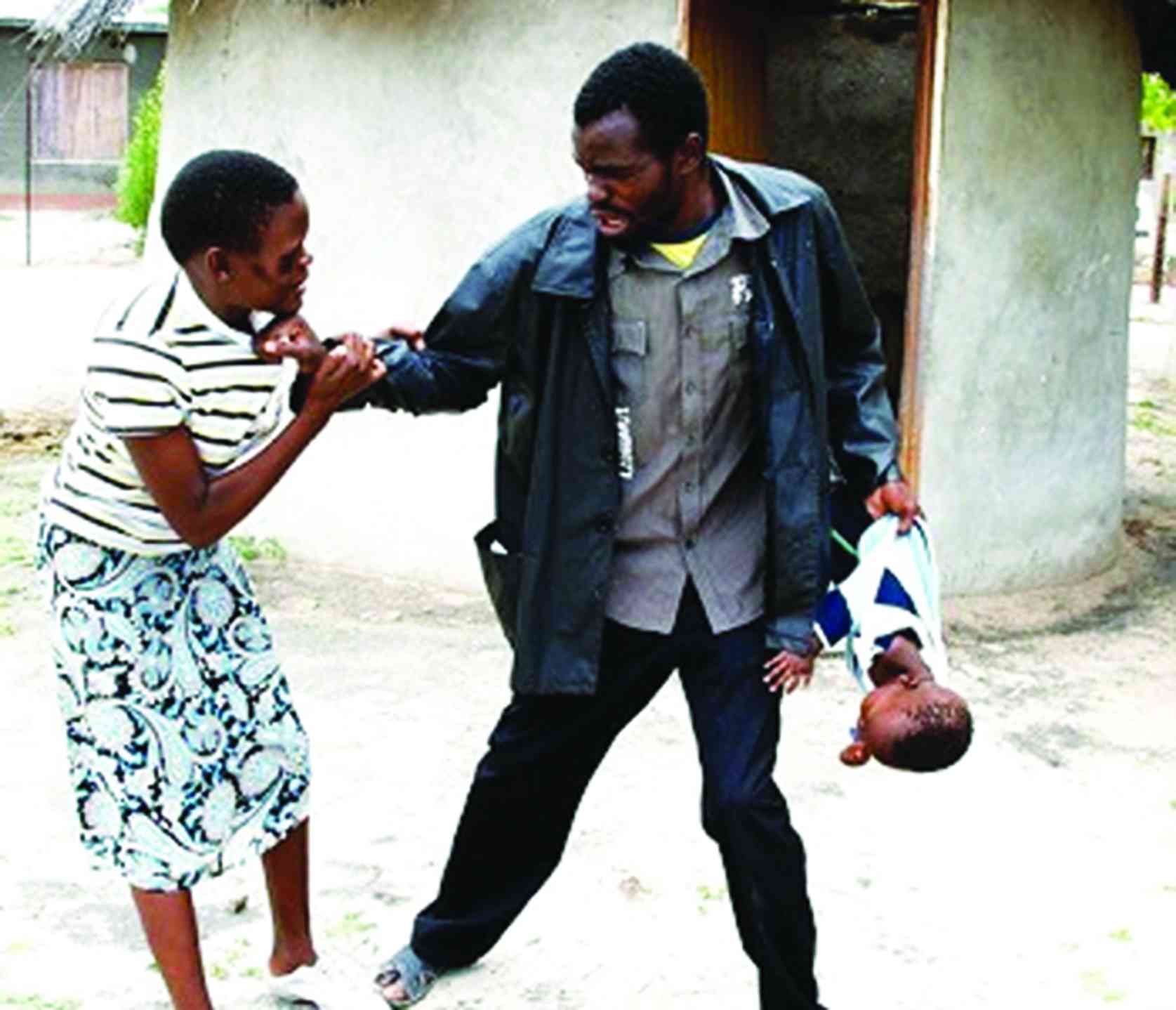

Thus far, the main damage has been to business and investor sentiment, especially abroad. The combination of the government’s use of the police and military and the Internet blackout is a severe setback not just to investment prospects, but also to the re-engagement process.

Businesspeople and economists are downgrading growth projections and raising inflation forecasts. Few take seriously the budget forecasts of 3,1% growth and 22,3% inflation in 2019.

Growth will fall short of target and could turn negative, depending on rainfall over the next three months, world trade growth, commodity price trends, and whatever catastrophic policies still lurk in government’s cupboard.

Rapid wage inflation and further workforce layoffs are inevitable along with industrial unrest, strikes and currency devaluation. At best, inflation is likely to average 40%.

As the economy slides further into stagflation, the New Dispensation promised by President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s government is in tatters along with budget forecasts and targets in the Transitional Stabilisation Programme.

The Davos trip, designed to showcase Zimbabwe as an investment destination, was the casualty of a remarkable succession of own goals in Zimbabwe and abroad — not least those scored in media interviews by Finance minister Mthuli Ncube, who demonstrated a quite spectacular foot-in-mouth capability.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The Western response has been mostly critical. Even the British, so pivotal in promoting Mnangagwa’s elevation to office, will now have to re-look at their covert support via the Department for International Development.

In South Africa, the main political parties and the trade unions have been highly critical, but an undeterred Ncube continues to talk up prospects of South African financial support.

With Plan A stalled, government is falling back on the Look East strategy joining Venezuela, not just in rampant inflation, but also reliance on dictatorial regimes in Eastern Europe, the Middle East (especially Iran) and China, further endangering the re-engagement process.

Meanwhile, the administration’s narrative is unchanged — Zimbabwe believes in democracy, human rights observance, transparency and the like, but government’s actions speak otherwise.

This poses formidable obstacles to minister Ncube’s promised reform programme, since in the absence of an international bailout, he is up the proverbial crocodile-infested creek without a paddle.

Economic prospects get bleaker by the week, leaving the authorities little option, but to refresh an “extend-and-pretend” strategy, incompatible with austerity.

The extend aspect involves explosive money supply growth, a ballooning domestic debt, issuing eventually-worthless government paper (Treasury Bills and 7% savings bonds), defaulting on TB maturities, and borrowing from political, offshore lenders such as Zimbabwe’s lender of last resort, Afreximbank.

Pumping liquidity into the system, regardless of the impact on the exchange rate, is underpinned by an incoherent cocktail of official handouts and subsidies, command agriculture, soft loan windows, import controls, protective tariffs, export and food subsidies and informal price controls.

The entire, ramshackle edifice is built upon opaque, increasingly complex and mutually-contradictory controls, including arbitrary import prioritisation by the central bank, interest rate caps, artificial bifurcation of bank deposits and, most recently, fuel duty rebates to those best able to pay the higher tax.

The extend system relies on “availing” funds — a favourite term of government and media alike — from a variety of mostly opaque sources in a vain attempt to pretend that policy is succeeding.

Fundamental to the strategy is an unsustainable exchange rate policy, now well past its sell-by date, conducted in a Tower of Babel atmosphere of confusion, denial and wishful thinking.

Pretence knows no bounds: the RBZ classifies real time gross settlement balances and TBs held by banks as “liquid assets”, which obviously they are not; audited corporate financial statements overstate revenues, profits, monetary assets and dividends; foreign investors are expected to believe that share prices on the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange are quoted in dollars; petrol queues are “psychological” as presumably are those for bread, and a bond note is worth the same as a US dollar.

Although the parallel exchange rate has plunged 60% since he took office, Ncube insists that it is stabilising, but since the local currency is at par with the US dollar, does it matter?

Pretending works only when the audience believes you which is why public relations is so integral an element. Until the 2018 elections, the Mnangagwa administration played this card effectively, thanks in no small part to the former British Ambassador Catriona Laing’s sustained disinformation campaign, weak-kneed business leaders and a slavishly obedient official media.

But since August when the wheels started coming off, it has become increasingly difficult to sustain the pretence. Anyone who watched the CNN footage of Ncube describing the Internet blackout as “strategic” and the use of the police and military to crush demonstrations as “opening up democratic space” can only have been dumbfounded that he could be quite so crass in destroying his reformist credentials.

In his austerity budget, Ncube promised to end the extend process, but within two months of the budget, he has been forced to back-pedal on public sector pay and allowances, and on unbudgeted spending for Zupco, civil service transport expenses, a fuel rebate scheme and wasteful offshore trips, epitomized by the Davos debacle. That there will be more backsliding can be taken as read.

Fortunately for the government, there is wiggle room in the budget because revenues from the regressive 2% transaction tax were under-stated by as much as $1 billion, while revenue from the fuel tax hike could add another billion, depending on how the announced rebate system operates. There will be revenue gains too from fiscal drag — higher income and consumption tax receipts due to inflation.

However, if spending keeps pace with 40% inflation, it will rise by over $3 billion, suggesting that the austerity budget will miss its deficit target.

Even if the budget deficit is kept to the forecast $1,55 billion — and since all the Treasury forecasts have already been seen to be inaccurate this is unlikely — there is still another $2,7 billion in debt repayments to be found, taking the funding total past $4 billion.

The minister announced plans to roll over — for which read default on — some debt repayments. Just how this will be done with inflation of more than 40%, and massively negative (minus 30% at least) real interest rates remains to be seen.

Private holders of TBs (over $3 billion) and the $2 billion in government’s 7% bonds will — if they are lucky — redeem their savings, on which they are earning hugely-negative returns, in money worth at least 40% less than when it was invested.

Factor in devaluation and Zanu PF will have decimated domestic savings, twice in a decade — no mean achievement.

The impact of such fiscal and monetary follies on savers, corporates and above all pension funds will be savage.

Indeed, it already is where banks and firms mark their monetary assets to market.

There is more to come: if and when Ncube launches his new, devalued currency, the holders of $10 billion in bank deposits, as well as those with TBs and savings bonds, will be outraged — sufficiently so for some to drag the government to the courts for repeatedly assuring everyone that the money in their bank accounts is in US dollars.

That, with this track record, not to mention 20 years of international default, the Mnangagwa administration expects foreigners or locals to lend it still more money highlights its tenuous grip on reality.

There are still some — asset managers, business leaders, diplomats and World Bank officials — who believe in an “economic” solution to the Zimbabwe crisis.

But with the New Dispensation on the rocks, systemic change going well beyond traditional economic reform programmes to embrace socio-political renewal is essential.

Those with even a cursory knowledge of corporate turnaround strategies know that merely changing the chief executive officer, especially with a carbon-copy, doesn’t work.

In Zimbabwe, the problem was far greater than the former president. It was, and still is, the system, which will not be changed by economic reform alone.