On June 29, 2016, the Constitutional Court of Zimbabwe will sit to consider the first constitutional challenge to the “national” school pledge. There has been a lot of discontent and commentary on the validity of the pledge on moral grounds, but in what follows, I attempt to provide commentary on a legal basis. The pledge in question reads:

Paul Kaseke

“Almighty God, in whose hands our future lies, I salute the national flag. Respecting the brave fathers and mothers who lost lives in the Chimurenga/Umvukela. We are proud inheritors of the richness of our natural resources. We are proud creators and participants in our vibrant traditions and cultures. So I commit to honesty and the dignity of hard work.”

What is a pledge? By definition, a pledge or oath is defined as a solemn promise or agreement to do something or to refrain from doing something, usually calling on a higher or divine power as a guarantor or witness to the pledge — an argument which shall become relevant later.

Pledges and oaths in the Constitution of Zimbabwe The 2013 Constitution of Zimbabwe, hereafter referred to as the Constitution, is the supreme law of the country and binds all people of Zimbabwe, organs of State and governmental agencies. The Constitution, therefore, overrides all other laws, regulations and policies. Section 60 of the Constitution accords each individual the freedom of conscience which includes “the freedom of thought, opinion, religion or belief”.

Section 60 (3) further states that parents and guardians of minors have the right to determine in accordance with their beliefs, the moral or religious upbringing of their children. The Constitution could not have been any clearer that the Primary and Secondary Education ministry cannot determine the moral or religious upbringing of minors without roping in the parents of such minors.

The claims by the ministry that the pledge is not religious are with respect, very unintelligible and ignorant. The definition of a pledge and/or oath inherently has religious connotations attached with a divine witness or guarantor being called on. As the current pledge stands, it unwittingly brings in religion to it and a simple dictionary check will prove this to be true.

The flaw of the ministry’s argument that the pledge is not religious is further seen in the invocation of “Almighty God” right at the beginning in the pledge, which, by very basic grammatical rules, entails who it is addressed to. This is a pledge that addresses God at some point in time — it is, therefore, a religious pledge or at least a pledge that dabbles with religion. To argue otherwise is, with all due respect, illogical.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Strike one: As noted above, section 60 guarantees freedom of thought and this freedom is extended to all persons in Zimbabwe including children. Freedom of thought includes the freedom against having ideas forced down on an individual and inadvertently, the freedom from indoctrination.

At this stage, I do not find it necessary for me to engage in the correctness of what the pledge states even though it contains several lies including that the children are inheritors of the natural resources — we know that only a few “special” Zimbabweans enjoy the wealth from our resources and have individual claims to the minerals. Ironically, the pledge speaks of honesty yet some of its provisions amount to false affirmations.

Strike two: Section 60 includes the freedom of religion, which is the main challenge that the case before the Constitutional Court is based on.

I won’t get into details here because the element of religion has been dealt with earlier suffice to say that the pledge is clearly a violation of the freedom of religion. The violation is twofold — it violates sacred areas of many religious tenets wherein pledging or making oaths is not allowed and also forces those who do not believe in God to call on a deity they neither know nor relate to.

Strike three: Section 60 (2) specifically prohibits the taking of oaths contrary to one’s religion or beliefs. By law, pupils can refuse to take the pledge — a point that the circulars sent to pupils and their parents is silent about. Again, the ministry has failed to respect the Constitution.

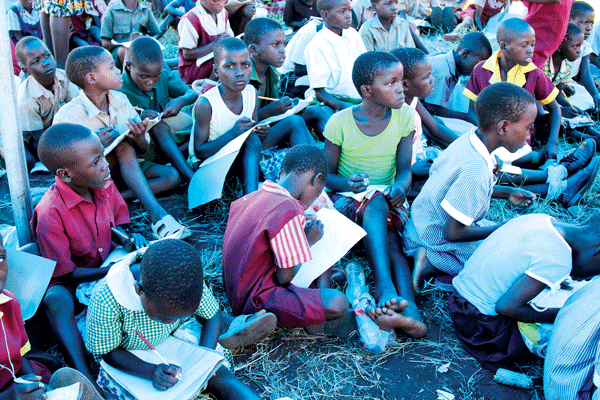

In addition, the ministry does not make an exception for non-Zimbabwean pupils who will be forced to pledge despite the pledge not being relevant to them.

Strike four: Section 19 (1) of the Constitution requires that any policies and measures taken by the State must ensure that in matters relating to children, the best interests of the child are paramount. This is further qualified in section 19(3) (b) (ii) which requires the State to take appropriate measures to ensure that children are not required to perform or provide services or work inappropriate for the children’s age, or place at risk, children’s well-being, spiritual or moral development. It’s fairly easy to see that the pledge potentially violates this section of the Constitution as well.

Strike five: Section 68 of the Constitution creates a constitutional right to administrative conduct that is lawful, reasonable, proportionate, impartial and both substantively and procedurally fair. The right is given effect to by the Administrative Justice Act, which defines administrative conduct as any action taken or decision made by an administrative authority.

For purposes of this discussion, the minister is an administrative authority. Among other things enshrined in the Act, the minister in making a decision which affects the rights, legitimate expectation or interests of people, must provide a reasonable opportunity for the affected parties to make adequate representations before a decision is made.

Furthermore, adequate notice of intended administrative action must be given to affected parties which in this case means parents. In terms of the minimum content of fairness envisaged in the Act, it is clear that the minister has, once again, violated this piece of legislation and on this basis alone, his actions can be said to be unreasonable and procedurally unfair.

Strike six: Section 194 of the Constitution requires that the ministry, among others, encourages the public to participate in policymaking. Again, the criticism is simple: in failing to consult extensively with parents and society at large, the ministry and its minister have failed in discharging their constitutional duties.

Strike seven: The Education Act which gives the minister much of his mandate has also been violated by the enactment of this pledge. Section 63 of the Act allows the permanent secretary to develop curricular but forbids the setting of different curricula for government and non-government schools on the basis of such a distinction. As has been reported, the pledge is part of a new curriculum, but interestingly, it only seems to apply to government schools. This renders the decision as unlawful on the basis of such differentiation.

Hopefully, the Constitutional

Court will breathe life into the Constitution and assert the various rights that have been brought to the fore by this pledge.

●Paul Kaseke (Snr) is a law lecturer at Wits Law School in South Africa, a legal adviser & consultant.